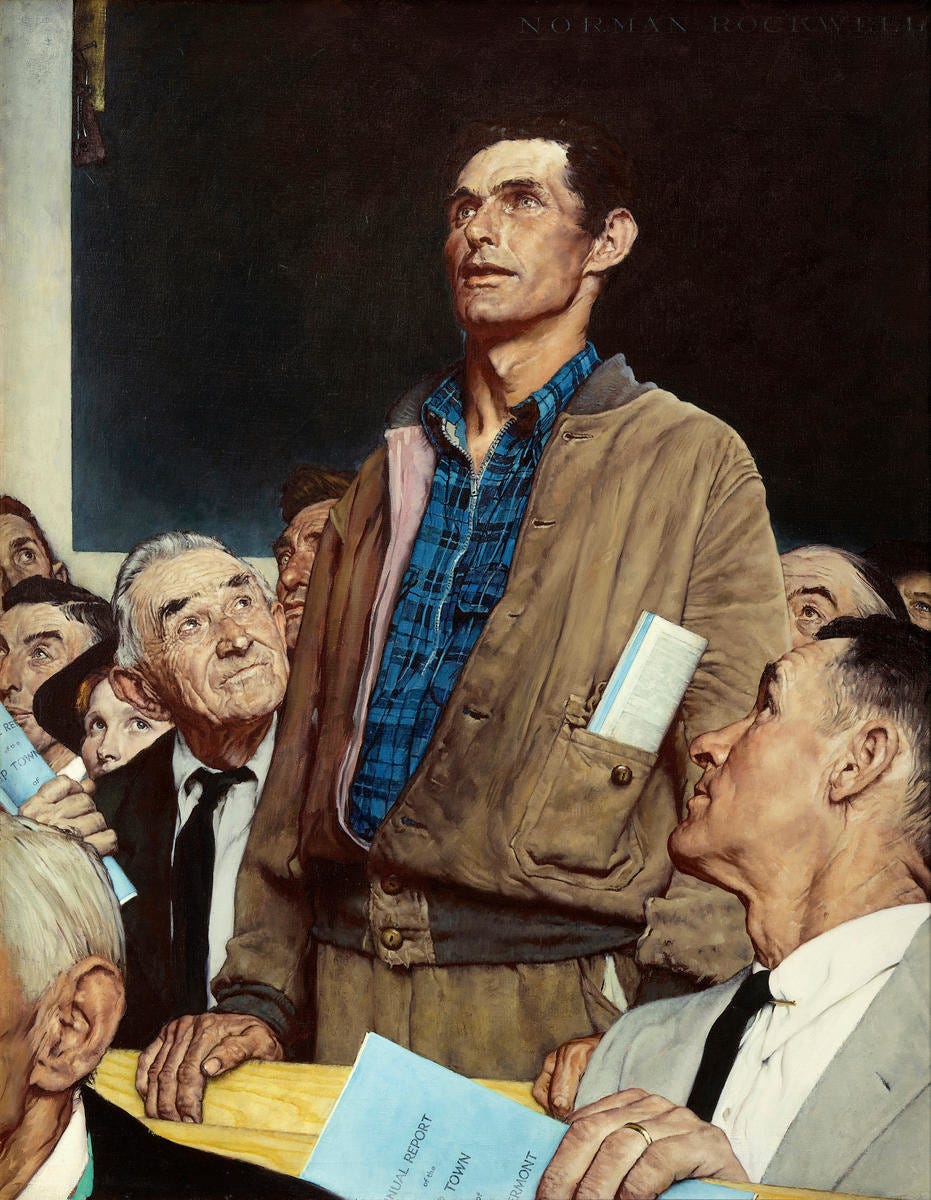

One of the best parts about writing Chalmermagne for the past couple of months has been the thoughtful responses I’ve received to my weekend scrawlings. While it’s always nice to get praise, I particularly appreciate the people who write in to explain why they think I’m wrong or where I’ve missed a trick. While I don’t always agree, I also realise that I can’t hope to see every possible angle of every issue, so it makes me sharper.

Every now and again, as some filler content to build reader community, I’m going to share a summary of the most interesting critiques, along with a few reflections.

Keep it coming!

Defensiveness about inoffensiveness

Seemingly people couldn’t get enough of my policy collab with Anastasia. I’ve heard stories of it being brought up at the start of roundtables … only for them to proceed along exactly the same pointless lines. As we warned in the piece, ‘winning mindshare’ isn’t the same thing as achieving change…

But Martin Koder, currently AI Governance Leader at financial messaging service Swift provided a thoughtful defence of one of our maligned archetypes:

All rings true apart from underselling the second archetype “The government is already doing it … and we agree”. This is actually an incredibly effective way of getting policy changed because you can reframe your ask as a better way to help policymakers supposedly deliver the objectives they already have. Such papers always begin with the same line "We welcome the [policymaking body]'s proposal for X. To help it deliver on its objectives of [motherhood and apple pie] we recommend some technical recalibrations to the [key threshold that impacts our bottom line] to ensure alignment with the [current meta policy fad of the most senior politicians in that jurisdiction] and consistency with [inevitable overlapping extant policy controlled by a different departmental head]. We present some new data demonstrating how bringing the threshold into line with [some other arbitrary classification already coded into law which happens to suit] could generate up to [gerrymandered but superficially defensible number] extra jobs 'n growth. I got swathes of legislation changed like that.

There’s probably a lot of truth to this. Framing your ask through the priorities of the people you’re trying to influence is obviously sensible. But the key here is having an ask.

Too much policy work unfortunately plays back stakeholders’ priorities and then forgets the next bit. This was the genre Anastasia and I really had in our crosshairs with this one.

I’m loving angels instead

Life hack: if you ever feel lonely, publicly call for a few tax breaks to be removed. You won’t be short of correspondence for weeks. My critique of the Enterprise Investment Scheme and Venture Capital Trusts - vehicles used by wealthy individuals in the UK to invest in high-risk companies while reducing their tax bill - provoked an avalanche of feedback.

Helpfully for the purposes of a summary, most of the criticism tended to focus on the same handful of points.

For example, Fred Soneya, Co-Founder and General Partner at Haatch covered two of the most common arguments: that I overlooked good funds and wasn’t harsh enough on bad practice in traditional UK venture.

I think some of your writing is spot on, and some is way off. That's coming from someone who manages a mix of capital, including SEIS and EIS.

I started to draft a response in full, including the areas I agree with you on (like fees—we charge no fees to portfolio companies) and areas I disagree on ("the incentive of an EIS fund manager is to deploy as much capital as possible and to protect the downside"—we delivered a 276x return, which was not an investment made with any view on how to protect the downside; we were all in personally), but I ran out of characters!

I also think it's easy to point the finger at the EIS Industry on points like fees, returns, incentives, and alignment. However, I can give you the same number of examples of GP/LP and PE Funds, which do precisely the same thing you're calling these managers out on.

There are also incentives that have been created (BBB ECF) that provide quasi-tax relief for investors to invest in venture funds, but are you saying that is okay versus EIS?

Meaning no offence to Fred, I didn’t find either of these arguments hugely persuasive.

Firstly, incentives aren’t the same thing as destiny. There can be good actors in a marketplace that incentivises bad behaviour, but they’re likely to be under-represented. We should commend the team at Haatch for not charging investee companies fees, but data in the piece showed that i) most EIS funds do charge fees ii) EIS funds are likelier to charge high fees than non-EIS funds.

In much the same way, a 276x investment (however impressive) in one EIS fund doesn’t negate lower returns among EIS funds in general.

To convince me that this argument is wrong, I would need to see evidence that I had either misunderstood the incentives or that EIS funds as a whole were much better actors than I realised. No one so far has made that case to me, but I’m open to it! Pointing to two or three better funds (as I did in the piece), however, doesn’t prove much either way.

Secondly, the attempt to turn my argument back on traditional UK VC overlooked that I’d made exactly this point in the piece!

Much of the bad behaviour I’ve described in this piece isn’t confined to EIS and VCT. There’s a longer piece to be written looking at how bad practice, founder unfriendly behaviour, and short-termism remains prevalent in the wider UK ecosystem.

If anyone thinks I’m too soft on the rest of the sector, they should check out the piece this Substack launched with. On day 1, I had a mailing list of … three people, so you are all forgiven for having missed it.

The most interesting critique came from Dom Hallas, the Executive Director of the Startup Coalition, which lobbies (very effectively) on behalf of the UK early-stage tech ecosystem. Professionally, I’ve been on the same side as Dom in many policy fights, so I’d have been surprised if he’d agreed with my desire to heavily curb a scheme many of his members have used.

Dom made several different arguments in an extended thread on X, which you should read in full, but two jumped out at me.

It misses the founders who are scrabbling to build and raise, not just the 1% that get transatlantic venture money at seed stage who will probably always get funded. It’s about building the widest funnel of risky early companies possible and then seeing which ones make the leap. A ‘startup Gini coefficient’ would show this ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ situation for founders and investors. 11x didn’t need a £250k SEIS round. But the haves aren’t the only people who could ever build businesses or invest in them. It’s great there are super successful founders and companies doing well - but try doing with no track record in the north of England and see how many Tier 1 term sheets you get.

I think the reference to transatlantic venture money is a bit of a misnomer, given that UK funds have raised tens of billions of pounds by themselves. The framing here risks implying that if you’re based in the north and Sequoia doesn’t come knocking, SEIS is your only other option. This might have been true of the 2004 UK ecosystem, but it rings less true in 2024.

At the risk of committing real venture heresy, I’m not sure we do need “the widest funnel of risky early companies possible”. I think we need a wide one, without artificial barriers, but funnel-widening isn’t free. The contribution of success stories versus the cost of the tax breaks and the money sunk into failures is something that we can measure. But, as I note in the piece, successive governments have shied away from robust economic evaluation in favour of polling the recipient of subsidies.

The other argument that jumped out was that funds are different. As Dom put it:

More businesses are taking ‘venture’ money and more funds have been created. They aren’t all doing the same thing and some of them don’t look much like the prototypical venture fund at all (though neither does Tiger Global or SoftBank). Ultimately this is probably a good thing - I think we’d all agree the financing for B2B SaaS businesses might not suit hardware driven climatetechs. But it clearly has quirks. Not all funding is the same (just like getting money from Sequoia vs getting it from a successful mid tier EU venture fund isn’t).

Tal Feingold, who coincidentally used to be with the Startup Coalition made an adjacent point:

The question I have is why is it bad to have a second tier of venture funds that aim for a lower return? Are you suggesting that the only companies worth funding are those that fit the trad venture model of hypergrowth?

While there is indeed more diversity in venture funding models, this doesn't excuse or explain why EIS funds specifically are underperforming. Many successful companies don't follow the “hypergrowth path”, but that doesn't mean that investors should accept poor returns. A climate tech start-up might generate big returns at a different pace to a B2B SaaS company, but to justify the high-risk and illiquidity of venture investing, the returns still need to appear at some point.

This is why ‘the second tier of funds’ doesn’t really wash with me: once you stop targeting outsized returns, the wheels start to come off the venture model. But if the product you’re selling isn’t “venture capital” and is instead “30% income tax relief”, then the calculation suddenly becomes different…

But these questions do point back to something I touched on in my first piece on this Substack: is the government too focused on VC-shaped solutions for early-stage businesses, even when they aren’t appropriate? Despite VC’s mindshare, it’s actually a pretty unusual way of financing a new business and isn’t the right vehicle for the vast majority of companies that are set up in the UK (or anywhere else).

Strikingly, all of the dissents focused on EIS. I haven’t received a single email, comment or reply defending the honour of VCTs.

Do you work at a VCT and feel maligned? Do you have a friend who works at a VCT who’s “alright when you get to know them”? Get in touch!

Defenceless?

Absolutely no one has written in to contradict my account of the poor state of UK defence. So either i) it’s as bad as I thought ii) there’s a secret plan they haven’t told us about but somehow a subset of Chalmermagne readers are in on it.

Based on my interactions with the Ministry of Defence to-date, I’d bet heavily on the former.

Exch-ch-ch-ch-changes

Last and, well, probably least the way it’s trending, is the fate of the London Stock Exchange.

James Clark, from Molten Ventures a (London-listed) VC firm was first to step to the plate, pointing out some of the reasons for the decline:

Hmm. Interesting but you've missed a number of fairly substantial contributing points:

- Regulatory compliance lumped onto UK listed companies is substantially heavier than the US. The LSE will point out SarbOx compliance as a reason not to list in the US, but a whole range of ESG and DEI compliance points have been imposed on UK listings in the last decade. This makes life as a UK listed company less attractive when combined with...

- Historic shift by the funds management industry away from equity and into debt. Equities used to be 50% of holdings of UK pension funds managers, it's now something like 5-6%. This huge shift has dragged down prices for UK listed companies and less money chasing that listed companies will drive down valuations.

- the final point which you've sort of addressed is the tendency for pretty much everyone to conflate the entire UK capital markets with "LSE". I guess LSE being a local monopoly doesn't really help here. But the lack of clarity makes finding the sources of the problem hard while offering the exchange itself as a convenient whipping boy.

James framed his response as disagreement, but I don’t dispute any of this - these likely all are contributing factors to the LSE’s decline. My purpose in the piece was less the why, which has been analysed exhaustively, and more the so what.

Even if we make our peace with the LSE’s poor record on tech, James makes the important point that we can’t take much comfort in its performance when it comes to old-school industrials, its historic bread and butter:

The other key point here is that tech specifically is a pretty global market and that global market is centered on the US, with exchanges in the US consolidating the gains of global tech companies. Other industries consolidate in different markets, LSE being a focus for mining and resources. With this in mind, LSE losing BHP Billiton in 2022 was a far greater loss than ARM or any single tech company.

Rodolfo Rosini, co-founder of UK-US chip start-up Vaire Computing, thought I was too blaisé about the decline of the LSE, and stressed the importance of an equity culture for policymakers and the public:

When I moved to the UK 20+ years ago, I made a list of countries and one of the key requirements was to have his own stock exchange. I do not believe you can build a credible ecosystem without some form of public markets. Even if you decide to list elsewhere (eg Israel). It is important because having an equity culture understood by the public and policymakers is super important. The UK is going in the opposite direction.

I don’t want to put words in Rodolfo’s mouth, but I assume that by ‘equity culture’, he means that a strong exchange with high levels of retail participation should create a healthier policy environment, as well as making it easier for companies to raise capital.

I think this tallies with the point I was trying to make about Sweden at the end of the piece. Its domestic exchange is strong, especially for smaller companies, even though runaway successes like Spotify have listed elsewhere. Israel, which Rodolfo cites, is similar. I think this is probably the ideal end state for the LSE (rather than trying to win over Arm-style tech listings), but I accept that we’re politically and culturally some way off from this happening. In my eye-rolling at old school asset managers, I probably understated this.

When it comes to how we bridge that gap, we should probably engage with Zachary Spiro’s work on LSE reform. I referenced his work with Onward and the TBI in the piece and he responded with a thread of his own.

He argues that I’m too optimistic about the prospects of smaller UK companies on US exchanges and that sub-index companies will likely get lost:

Take analysts:

The average S&P 500 firm - 23 analysts

The average Russell 2000 - 6

Russell 2000 firms w/ $50m-500m market cap - just 4

What does this mean? It means that you can't just list as a sub-index UK company in the US and expect buckets of analysts/liquidity to follow you around. If you want US markets to pay attention to your IPO, you need a good reason for them to do so.

He points out that:

UK firms that list in the US *look different* to the ones that list in the UK.

They have more US revenue, and have probably already built relationships with US investors. [...] there will be some UK companies where listing in the US isn't the right thing - e.g. maybe their revenue is too EU-based.

My framing about the decline ‘not mattering’ was probably a touch flippant and Zach’s point is basically fair. A company that reaches IPO without significant connection to US investors will probably fall into that ‘well-suited to a Swedish-style exchange’ model. This is simply because few companies set to be global venture-scale winners usually reach IPO with no relationships with US investors.

Hopefully, the UK adopts the reforms that Zach’s paper outlines - alternatively, the companies could just go and list in Sweden. As the FT long-read on Sweden’s stock market notes, they’re not choosy about wooing small to medium sized foreign firms. UK asset managers take note.

Bonus segment: maybe the real regional subsidies are the friends we made along the way

My work off the stacks about UK tech policy didn’t attract a universally positive response. The piece contended that the government didn’t approach tech policy as tech, but instead treated it as a poorly-defined extension of economic policy.

Tom Forth, the CTO and Co-Founder of The Data City, took exception to my suggestion that this was primarily regionally-focused:

Don't get it at all. The claim is that "the UK has spent billions to build a machine for distributing regional subsidies" and yet the two examples of what we've actually built are in central London. Where is the regional subsidies? When do I get my regional subsidies in Leeds?

It’s worth reading his longer follow-up piece, which makes the argument that opponents of regional R&D subsidies “don’t think that putting something in London by default is regional development activity. They should.”

He notes that:

In data, tech, and now AI the UK government has consistently tilted the playing field in favour of London. The Open Data Institute, Tech City, Tech Nation, The Digital Catapult, The Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, The British Library, The Alan Turing Institute, The AI Safety Institute, ARIA, and much more have been placed in the capital. The indirect government subsidies on offer in London make it ever more rational for British talent and ambitious companies elsewhere in the UK to relocate there.

I have a degree of sympathy with this, and in retrospect, I would probably take the word ‘regional’ out of my original sentence. This was lazy drafting and probably stems from staring too much at “regional venture capital funds” and other doomed government interventions of the 2000s for my first Substack piece.

I think the UK is a stupidly centralised country, which has negative economic and political spillovers that you can’t miss. I’d be up for dynamiting a significant proportion of the ‘London subsidies’ on Tom’s list and sowing salt where they stood, simply because I don’t think the orgs achieve much. But in my new devolved, smaller state Britain, am I up for a better geographical distribution of institutions? Sure.

I can’t promise that masochistically reviewing all your criticism will be a very regular feature, but if you like it, hit reply and let me know. In the meantime, I probably have one more piece left in me before the end of the year.

See you next time!

Disclaimer: These views are my views or those of the people leaving comments. Unless they left them ironically or didn’t mean them, in which case, they should put more thought into how they present themselves in public forums. But more importantly, these aren’t the views of my employer or anyone who didn’t leave a comment. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.