Introduction

The UK’s national AI institute is in crisis. Despite receiving a fresh £100 million funding settlement in 2024, the Alan Turing Institute (ATI) is gearing up for mass redundancies and to cut a quarter of its research projects. Staff are in open revolt.

In 2023, when generative AI fever swept the world, far from taking centre stage, the ATI found itself playing defence. A report from the Tony Blair Institute argued that:

While industry figures have predicted some advances and privately warned of major risks, existing government channels have failed to anticipate the trajectory of progress. For example, neither the key advance of transformers nor its application in LLMs were picked up by advisory mechanisms until ChatGPT was headline news. Even the most recent AI strategies of the Alan Turing Institute, University of Cambridge and UK government make little to no mention of AGI, LLMs or similar issues.

Martin Goodson, then of the Royal Statistical Society, dubbed the ATI “at best irrelevant to the development of modern AI in the UK”.

The criticism hasn’t slowed. Matt Clifford’s AI Opportunities Action Plan recommended that the government should “consider the broad institutional landscape and the full potential of the Alan Turing Institute to drive progress at the cutting edge”. While Clifford was too diplomatic to say the quiet bit out loud, in government speak, this is code for suggesting that the ATI was not fulfilling its intended purpose.

UK Research and Innovation, the UK’s main research and innovation funding body, is running out of patience. Its quinquennial review of the ATI, published in 2024, was politely scathing about the institute’s governance, financial management, and the quality of its most recent strategy (dubbed Turing 2.0).

There aren’t many areas of consensus across the UK’s fractious tech community, but the ATI has come to play an oddly unifying role. From left to right and north to south, there’s a sense that the institute is running out of friends and time.

While the median founder, investor, or civil servant will cheerfully roll their eyes at the mention of the ATI, what’s less understood is why the UK’s national AI institute has proven such a flop, despite spending over quarter of a billion pounds since its inception. To piece this together, I’ve spoken to current and former Turing insiders, figures from the world of research funding, academics, and civil servants.

Set up to fail?

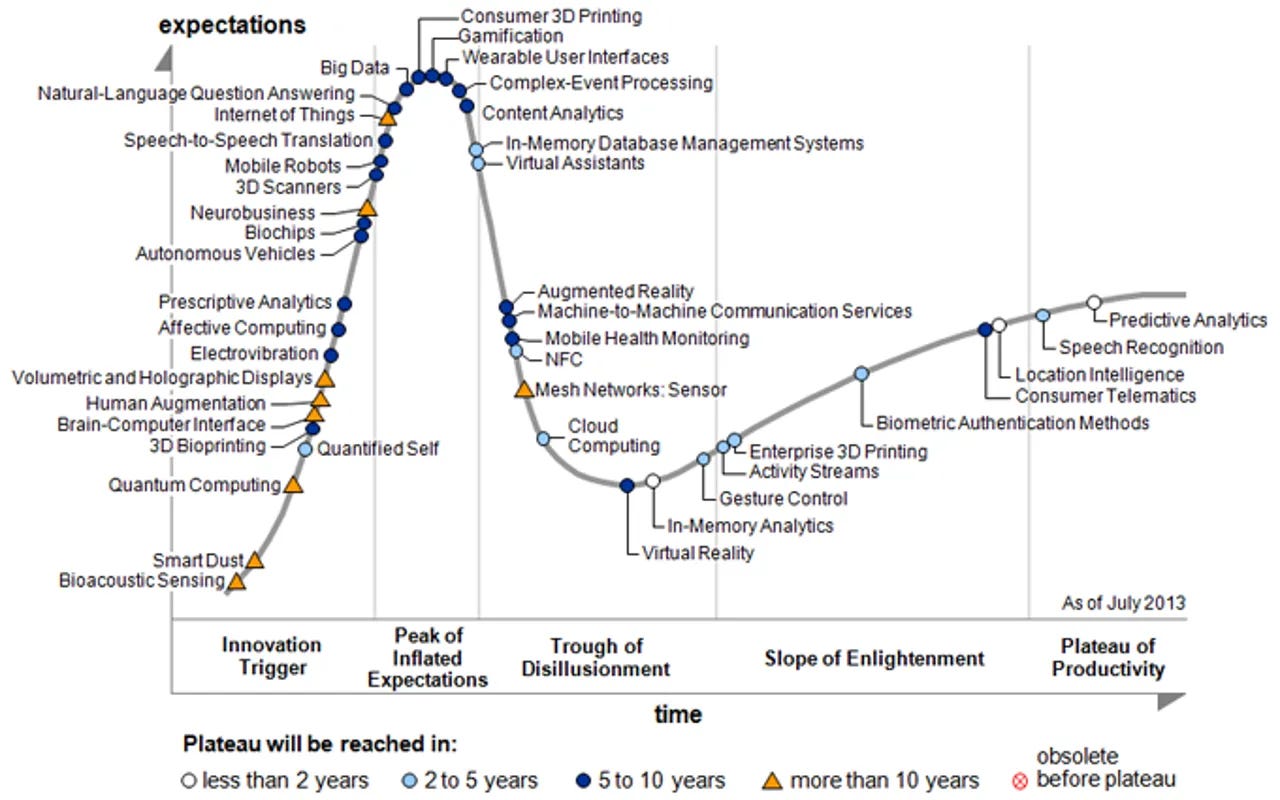

To understand the ATI, we need to understand the circumstances of its creation. Back in 2014, we had hit the peak of the ‘big data’ hype cycle.

As data storage costs tumbled, big tech companies printed money, and the cloud became the rage - the UK Government decided it wanted a piece of the action. ‘Big data’ had been identified as one of the UK’s ‘Eight Great Technologies in 2013’, unlocking new funds for consultancies to produce pdfs on public sector innovation.

In the 2014 Budget, George Osborne announced that the UK would invest £42 million over five years into a data science institute, dedicated to the memory of Alan Turing. From day one, the goals of the institute were nebulous. The official government announcement stated that the institute would “collaborate and work closely with other e-infrastructure and big-data investments across the UK Research Base”, as well “attracting the best talent and investment from across the globe”.

The task of bringing this ambition to life fell to the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), a powerful public body tasked with allocating money to research and postgraduate degrees. In July, a few months after the Budget announcement, the EPSRC called for expressions of interest from university partners. It would go on to announce Cambridge, Edinburgh, Oxford, UCL and Warwick as its initial partners following a competition to which over 20 universities applied. It has since expanded its university partnerships to a network of over 60.

The government announced that the ATI would have a headquarters in the British Library in London (after turning down a bid from Liverpool), along with “spurs” in businesses and universities. This would “bring benefits to the whole country … including in our great northern cities”, despite no academic institutions from the latter making the cut.

Creating a national data science institute in partnership with some of the UK’s top universities might seem like a logical move. But arguably, this was the root from which all of the ATI’s ills stemmed.

A virtual institute

By outsourcing the institute to the universities, the EPSRC guaranteed that the ATI would always be less than the sum of its parts.

In the words of one senior academic: “The EPSRC wanted to establish a data science institute, but didn’t want to take on the long-term responsibility of funding and governing it … the landscape is filled with institutions that have been offloaded onto higher education”.

Universities contributed research muscle, but if an academic became a ‘Turing fellow’ or led a programme at the institute, they would retain their primary affiliation and would often work no more than a couple of days a week at the ATI.

This made it hard to build a research culture or set of owned capabilities. One ex-ATI staffer described the institute as “a set of sole traders … all self-interested”, who had “little incentive to collaborate”. While they remembered some of their former colleagues contributing, others treated the ATI as “a fancy coffee room”. A current Turing staffer said, “the academics just have no skin in the game”.

A senior research funder adds, “If you’re not aiming to build an institutional culture, then why set up an institution?”

Another source described how “it was conceived as a weird virtual institute”, which meant that “universities bickered with each other and then with the EPSRC. There were too many cooks, no core of people who could deliver stuff, and they [the ATI] never had their own strategy.” To illustrate the many cooks, there are 25 people who sit across the ATI’s three advisory boards, only one of whom works for a frontier AI lab.

There was no bigger source of bickering than money. While the EPSRC stumped up much of the ATI’s money, partner universities were big financial contributors. They expected their money back - with interest.

Each partner university nominated a ‘Turing liaison’ to act as the contact point between their university and the institute. In reality, the liaison director’s job was to maximise the amount of money awarded to their own institution’s research. As our former Turing insider from before puts it, “the original five universities were customers and suppliers”, this “created an obvious conflict of interest”.

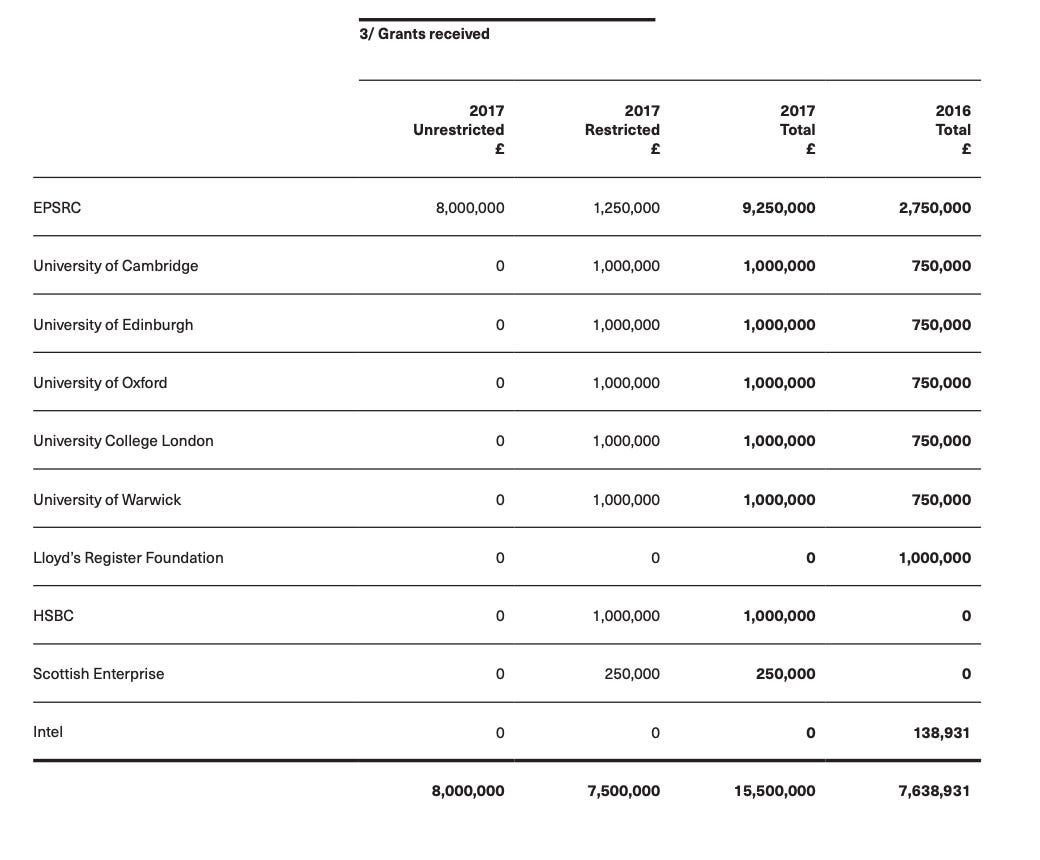

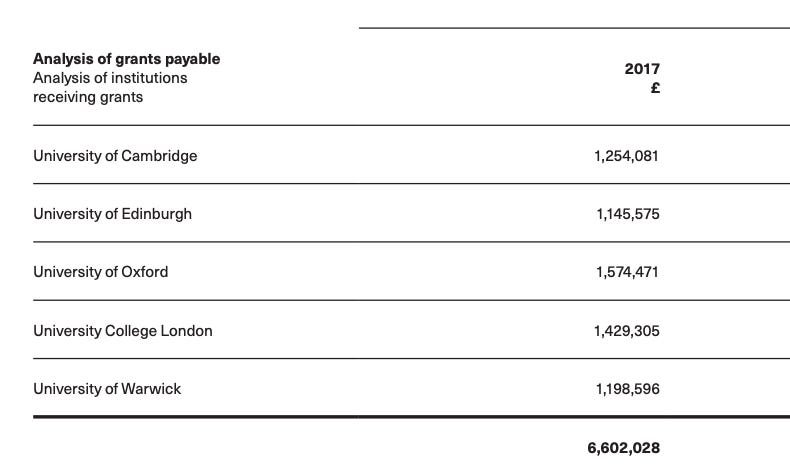

If we take 2017 as an example:

The original five universities paid in a million apiece, and made a good return on their investment.

As the ATI’s group of partner universities expanded, the original five were the predominant beneficiaries. While they took a ‘loss’ on the first couple of years of contributions, they soon handsomely profited. In 2019, for example, the five put in £5 million and received back £9.8 million in grants. The new universities in the coalition who had contributed £8 million benefitted from less than £4 million.

It likely doesn’t hurt that the five founding universities hold the majority of seats on the ATI’s board of directors, along with veto rights.

UKRI has grown weary of this setup, with the quinquennial review warning that “there is a clear need for the governance and leadership structure to change fundamentally to reflect a more representative set of stakeholders … the Institute must have an impartial governance arrangement which is fit for this purpose, which follows best practice for similar public investments, and be shown to represent the concerns of the whole community”.

A national institute for hire

How were the universities ‘profiting’?

In part, the ATI acted as a vehicle for shuffling public money from one institution to another. But from day one, the institute had commercial ambitions. The ATI quickly established itself as a taxpayer-subsidised technology consultancy.

As one former ATI staffer put it, the pressure from universities to maximise returns meant that the institute would “go where the money is … it didn’t smell right”.

From 2016, it began striking partnerships with outside organisations. Work the ATI undertook included flight demand forecasting with British Airways, fraud detection in telecoms with Accenture, and improving Android game recommendations for Samsung. Other work the ATI conducted, while not directly sponsored by industry, clearly was designed with commercial applications in mind, such as exploring the correlation of viewers’ emotional journeys with the commercial success of films.

This is not to call into question the merit or rigour of any of this work. But it is reasonable to ask why a national institute was conducting it and how this was building nationally-useful capabilities. Industry could easily commission academics directly or pay consultancies to conduct this work for them.

The ATI was also at an, arguably unfair, advantage in this respect. Thanks to its generous upfront funding and academics’ comparatively low dayrate, the institute had a price advantage versus its commercial rivals. It didn’t hurt that they could, as an academic put it, “hawk the national institute” and “trade off the Alan Turing name”.

Missing the AI boom

In 2017, the ATI added artificial intelligence to its remit at the request of the government. The institute, however, struggled to make an impact in its new role.

Again, the universities bear a significant share of the blame.

Despite the frequent use of the ‘world-leading’ sobriquet by the government, UK universities were not at the frontier of contemporary research on deep learning. Senior British computer science academics’ strengths historically lay in fields like symbolic AI or probabilistic modelling. They initially viewed the work of DeepMind and others as little more than a glitzier version of 1980s work on neural networks. If you look at leading UK university computer science curriculums across 2018-2020, deep learning scarcely features. Senior UK academics were sceptical about how much deep learning could scale and some even forecast an ‘AI winter’.

Michael Wooldridge, a senior Oxford academic and director of Foundational AI Research at the ATI was among the sceptics.

As late as 2023, he was still playing down recent innovation, dismissing AlphaGo as an artifact of scale. In the same piece, Wooldridge dismissed LLMs as “prompt completion … exactly what your mobile phone does”. In response to the DeepSeek mania in January of this year, he said, “I confess I hadn’t heard of them”. This oversight might have been excusable had it not been made by the most senior AI researcher at a national AI institute.

At the ATI’s flagship annual AI UK conference in 2023, the single talk on generative AI (“ChatGPT: friend or foe?”) was delivered by Gary Marcus, a prominent LLM sceptic who had argued a year earlier that deep learning was hitting a wall.

This dismissiveness towards the latest AI research was fused with, as an ex-staffer puts it, “a left-leaning middle management layer … who wanted to narrate the public conversation”. As a result, the ATI positioned itself as “the police officer, not the innovator”.

This is reflected by the institute’s output from 2018 onwards, which skewed heavily towards a specific ideological interpretation of responsibility and ethics.

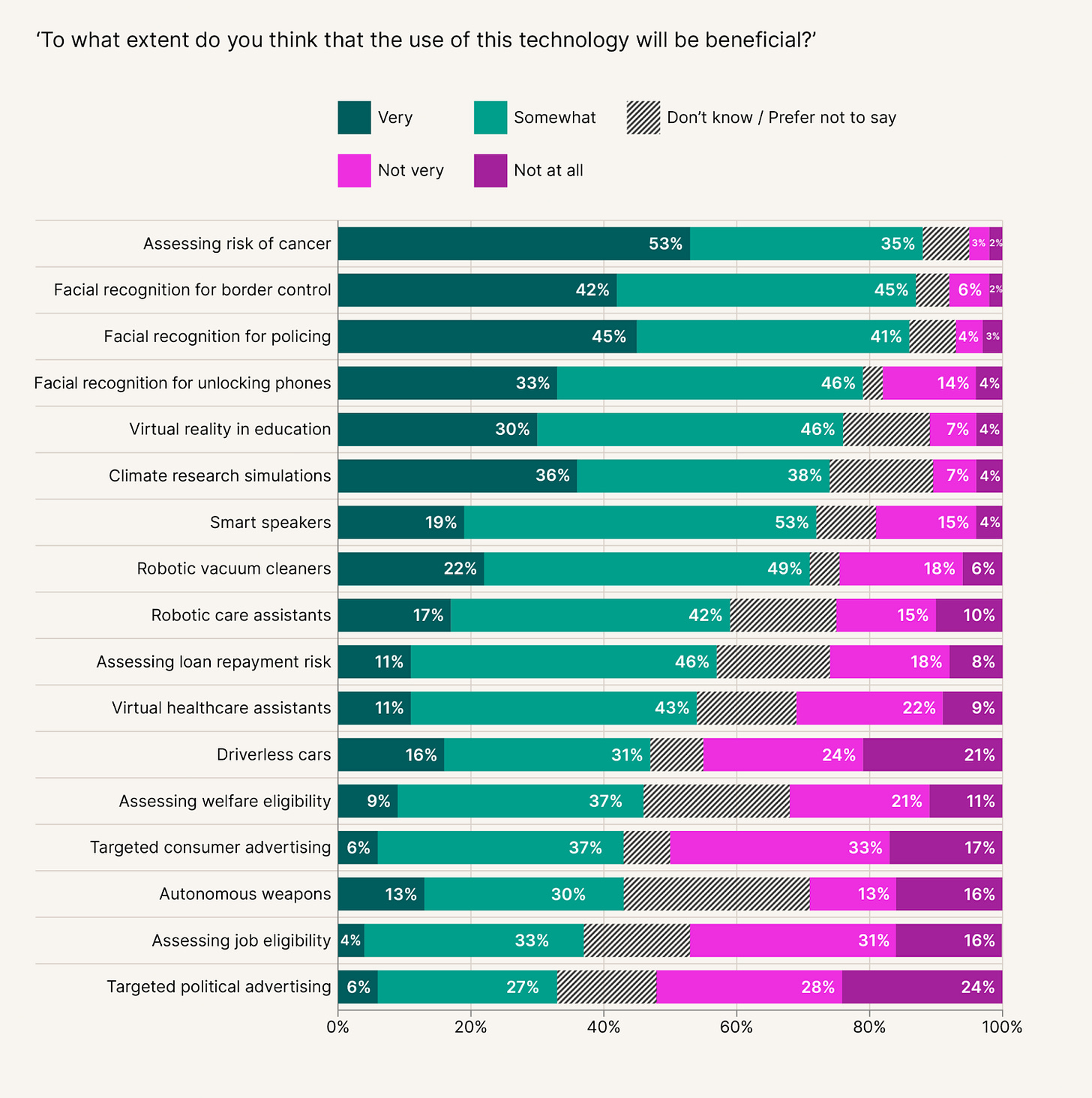

There is, of course, nothing wrong with promoting the responsible use of AI or ethical development practices. Problems like bias are well-documented and have caused real-world harm. The ATI’s work, however, tended to focus less on building technical solutions and more towards the banal restatement of well-known problems (e.g. the risks of facial recognition in policing, the importance of data protection), unremarkable surveys of public opinion (people think detecting cancer is a good thing, but are nervous about bombing people), or highly politicised content that seems better suited to a liberal arts college.

A current member of staff observed that “the public policy programmes have some of the wooliest outputs imaginable”.

A drinking game based on mentions of ‘stakeholders’ or throwaway references to the need to ‘consult civil society’ would prove fatal.

This cultural bias was also self-fulfilling. As another former insider put it, “many technical academics just got fed up and walked away”. Another bemoaned how the “institutional capture by sociology is total”.

A national institute could, of course, make practical contributions on these questions. The Toronto-based Vector Institute, for example, built an open source tool that not only classifies biased training data, but also debiases it. That said, the ATI did build a closed source bias classifier for … its customers strategic partners at Accenture.

The ATI’s decision essentially to ignore much of the cutting edge work coming out of DeepMind and US labs meant that its leadership was asleep at the wheel as the generative AI boom got underway.

Until early 2023, the ATI’s output did not mention language models at all. In response to criticism, the ATI’s most senior researchers argued that LLMs had caught the whole world by surprise, so it was unfair to single them out.

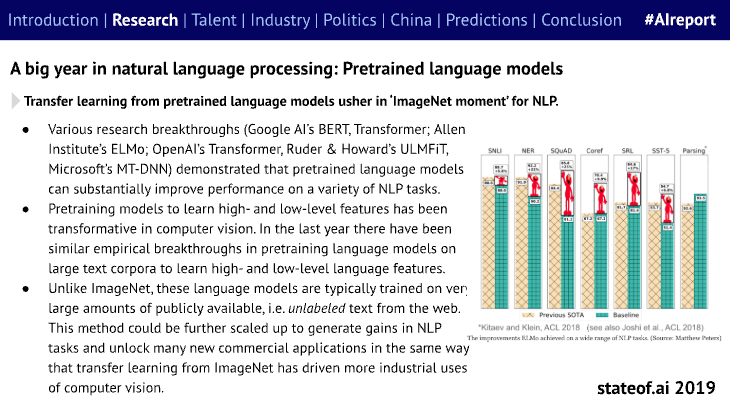

While these models may not have entered the public consciousness pre-ChatGPT, it is unserious to suggest that they were somehow secret. Nathan Benaich and Ian Hogarth covered them in the 2019 installment of their State of AI Report.1 The Report has been widely read in AI circles for over half a decade. OpenAI’s initial decision not to release GPT-2 earlier that year was covered in UK national newspapers. What the ATI dubbed hindsight, others could term dereliction of duty.

When the government did need to call on the ATI for help, they were frequently underwhelmed. A former government insider who requested the ATI’s help on Covid-related technical analysis was horrified when the institute took 18 months to complete the work. Based on their own technical background, they believe a competent team could have managed it in one. By the time they received the output, the pandemic was over and it was no longer useful. They consistently found the ATI’s leadership more interested in the amount of money they could charge than in how to be the best possible partner.

This is a wider disease in the UK ecosystem. The government’s (now defunct) AI Council, primarily staffed by the great and good of UK academia, spilt much ink on the subject of responsibility, but failed to include LLMs in their 2021 roadmap. One academic familiar with the work of the council said that, “On some level, these people still don’t believe AI is real. They were telling the government that there was nothing novel about the transformer [the architecture that underpins LLMs] and that they should be focused on regulating upstream applications”.

There is little sign that UK academia has learnt its lesson. In 2023, UKRI staked Responsible AI (RAI) with £31 million of public money.

RAI was born after the new Department for Science Innovation and Technology lent on UKRI to free up money, so that it could showcase investment in the UK’s new ‘Five Critical Technologies’ - the government’s latest set of priorities for tech policy. UKRI scraped together a £250 million Technology Missions Fund from old budgets, but struggled to find investable projects.

UKRI turned to the universities for help and a coalition, led by Southampton, conceived of Responsible AI. RAI, the Technology Missions Fund’s flagship AI investment, has gone on to fund a series of Turing-esque projects, including yet more responsibility guidelines, the use of music to keep tired drivers awake, and whether citizens should have personal carbon budgets. RAI’s first annual report lists six achievements, two of which boil down to hosting roundtables and presentations. The purpose of the Technology Missions Fund was to drive the development and adoption of new technology, not to, as RAI put it, “connect the ecosystem”.

As ChatGPT stunned and terrified Whitehall in equal measure over the course of 2023, the ATI found itself on the defensive. But its defence frequently underscored the problem. Then director and chief executive, Adrian Smith said, “We have delivered numerous briefings to government officials, hosted training and contributed to several roundtables on this topic, as well as offering commentary through media and broadcast interviews.” The Turing 2.0 relaunch strategy from the same year contains a single reference to LLMs across its 66 pages.

There are welcome signs that academia’s grip is being broken. Dissatisfied with the advice they received from the universities, the government established the UK AI Safety Institute (recently renamed to the ‘Security’ Institute) in November 2023, to bring it closer to the work conducted in frontier industry labs.

As the highest levels of government grapple with the interdisciplinary risks, such as biosecurity, that have risen from a rapid acceleration in capabilities, the universities remain unrepentant. If anything, senior academics have prided themselves on their opposition to the new direction and have vented their frustration at losing their place in the Number 10 rolodex.

Dame Wendy Hall, a senior computer scientist and former AI Council Chair turned RAI leadership team member, has condemned the “tech bro takeover” of AI policy and accused the government of ignoring cutting-edge work in universities. Professor Joanna Bryson, co-author of the UK’s first national-level AI ethics policy in 2011, recently derided AI safety as “transhumanist nonsense”. Neil Lawrence, who holds a DeepMind-sponsored professorship, slated the UK government’s “appalling” discussion of AGI and accused it of celebrating big tech companies for “solving problems that no one ever knew they had”.

It is, of course, possible to object to specific claims made in AI safety research or to disagree with researchers concerned about existential risk. But the response of academia’s old guard has been to ignore the substance of this work and instead to designate the entire field as ideologically suspect.

The ATI itself doesn’t seem to have learned either. Its 2025 AI UK conference didn’t feature a single researcher from a frontier research lab this year.

What could have been?

Amidst a maelstrom of stakeholder wheelspinning, one area of strength stands out in the ATI’s work: defence and security. While sitting under the ATI umbrella, the defence and security programme has its own team, research agenda, and operates independently. Thanks to its ties to industry and the intelligence agencies, it’s also the least ‘academic’ part of the ATI.

Its work includes directly supporting the application of technology to national security problems, AI research for defence, and partnering with allies in the US and Singapore.

The most publicly visible manifestation of this work is the Centre for Emerging Technology and Security (CETaS). Driven by a clearer sense of mission, CETaS has built up a degree of community respect that the ATI proper has not. A security researcher at Google DeepMind described them as “great… the best bit of Turing”. An academic with experience of working with the national security community said that “they just quietly get on with it”.

Their output consistently engages with frontier research, provides specific and differentiated advice to industry (e.g. on the need to integrate the UK and Korean semiconductor industries), and empirically analyses popular memes (e.g. the (lack of) impact of AI-enabled disinformation on elections) as opposed to parroting them.

CETaS also … just makes sense. There are obvious advantages a public body has when it comes to working with the national security community. When it comes to broader ‘ethics’ work, which any number of think tanks or advocacy groups could do, the relevance is less apparent. Similarly, the intersection of AI and health, another ATI ‘mission’, more logically sits in universities with links to hospitals.

If the government were to re-evaluate the ATI, there would be a strong case for preserving CETaS, potentially as a sister organisation to the AI Security Institute.

A system failure

The story of the ATI is, in many ways, the story of the UK’s approach to technology.

Firstly, drift. The UK has chopped and changed its approach to technology repeatedly, choosing seven different sets of priority technologies between 2012 and 2023. Government has variously championed the tech industry as a source of jobs, a vehicle for exports, a means of fixing public services, and a way of expanding the UK’s soft power. These are all legitimate goals, but half-heartedly attempting all of them over a decade is a surefire means of accomplishing relatively little.

Connected to this is our second challenge: everythingism. My friend Joe Hill described this aptly as “the belief that every government policy can be about every other government policy, and that there are no real costs to doing that”. This results in policymakers loading costs onto existing projects, at the expense of efficiency and prioritisation.

As the ATI’s original goals were so vague, it was a prime target. Even before the ATI was up and running, the government announced that it would also be a body responsible for allocating funding for fintech projects. It then had a data ethics group bolted onto it as a result of a 2016 select committee report. As one ex-insider put it, “there was never a superordinate goal”.

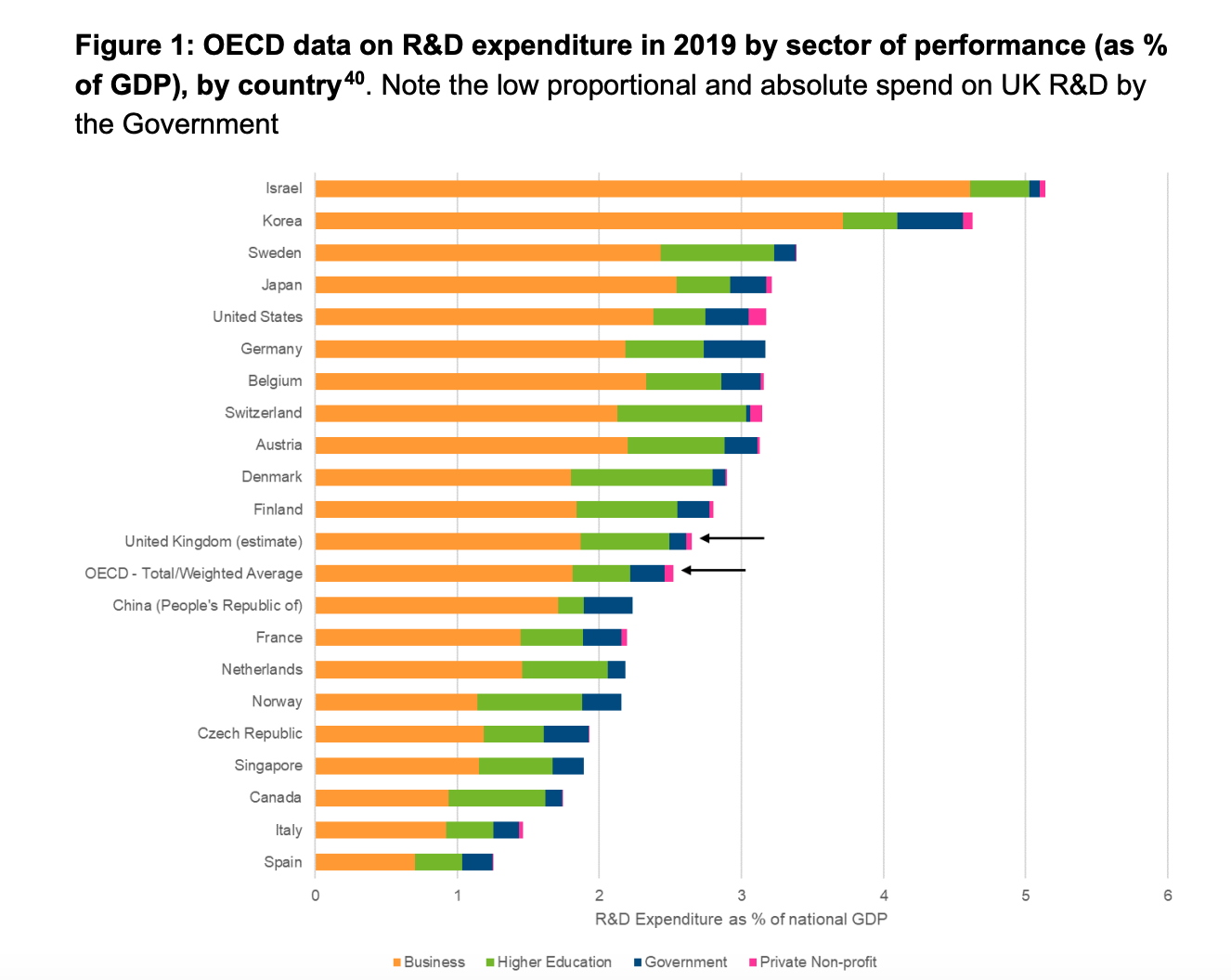

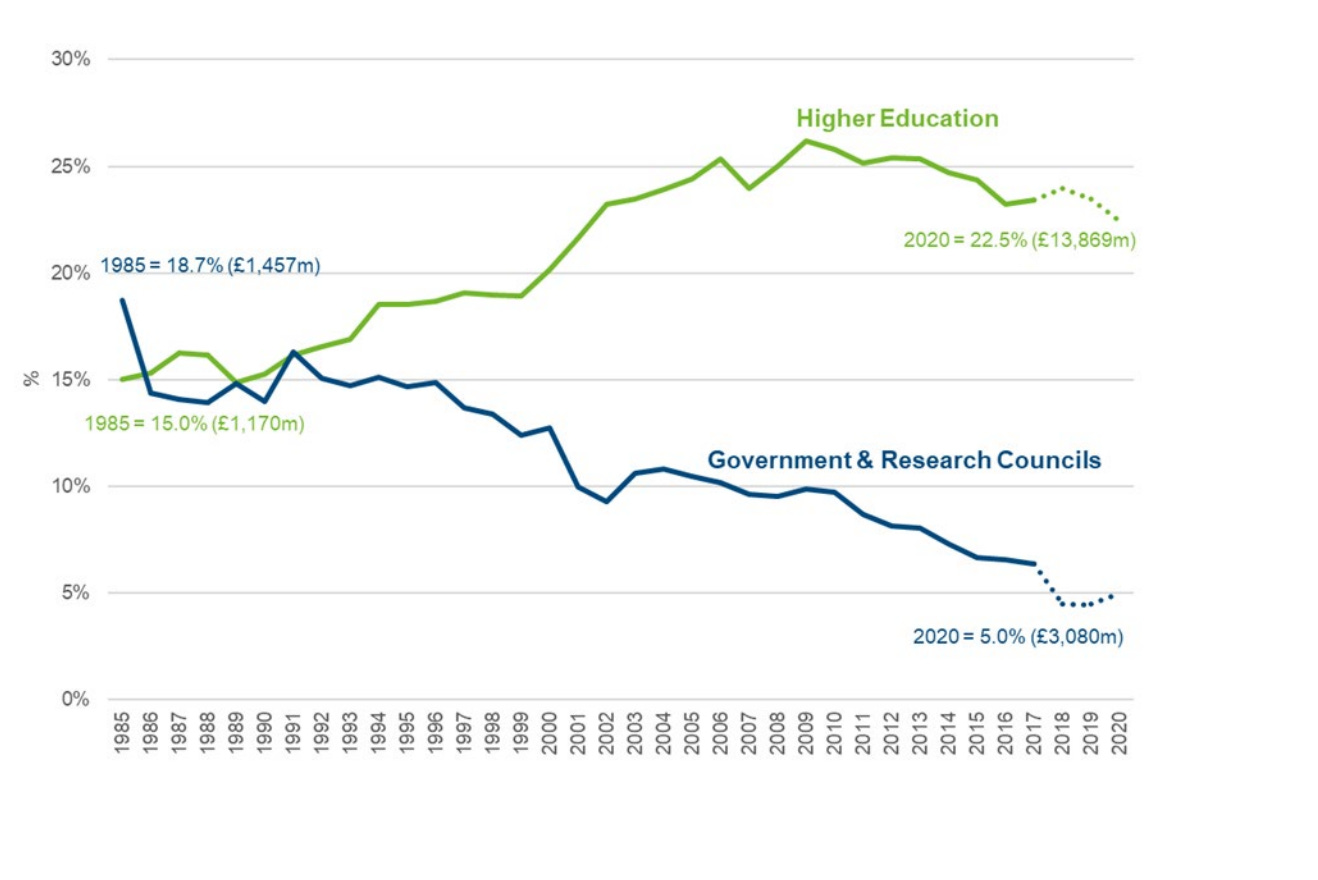

Finally, the perils of the UK government’s dependence on the country’s universities for research. The UK has historically channelled 80% of its non-business R&D through universities, versus 40-60% for many peer nations.

This is the product of policy choices made in the 1980s onwards, which prioritised funding research in universities over public sector research establishments or government labs. This started under the Conservatives, but continued under Labour with the first Blair Government’s decision to close and partly privatise the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (then the UK’s largest government R&D body).

The other driver is the 2002 introduction of the full economic costing model (fEC) for research funding. When a research council awards a grant to a university, they do not have to fund it in full. They typically only cover 80% of the fEC, while universities pay up the rest. In practice, research councils will often try to drive their share even lower.

Unlike other institutions, universities are able to cross-subsidise research costs from other income sources, such as international student fees. They also benefit from an annual £2 billion bloc grant that helps them make up any shortage. This system favours universities over everyone else and incentivises the worst kinds of grant-chasing.

It’s perhaps why some of the more interesting institutes and labs attached to universities are the product of philanthropy, rather than the usual cycle of research council allocations. The Gatsby Unit at UCL, where Demis Hassabis completed his PhD, was funded by David Sainsbury. The Peter Bennett Foundation funds institutes at Cambridge, Oxford, and Sussex. A source in the research funding world put it more bluntly: “Rich people can defy university shitness… the Turing is the product of academic capture and the professors that run research councils.”

In essence, the universities ended up in charge of the ATI, because government policy ensured that there was no one else with the necessary scale and resources to take on the responsibility. It just so happened that they were also uniquely ill-suited to the task. It’s not a coincidence that the most functional arm of the ATI was the one with the least academic involvement.

The most common theme of Chalmermagne posts so far has been institutional failure and the legacy debts it creates. If you look across reams of UK policy, whether it’s in technology, defence, or finance, you see the same thing: a penchant for symbolic announcements, a bias towards outsourcing to ‘stakeholders’, and a reluctance to kill off bad policy long after any reasonable trial period.

Considering how the UK treated Alan Turing while he was alive, he deserved a better institute to honour his memory. But then again, government is slow to learn from its mistakes.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views only. They are not the views of my employer, any stakeholders, or civil society organisations. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Disclosure: I previously worked for Nathan at Air Street Capital and supported on the 2023 and 2024 editions of the State of AI Report

I was the first (and at the time) only industry fellow at the ATI when it opened. I was involved in the discussions before it was proposed to the government. Still I actually think that I got the fellowship because I was the only person to apply, which I really found quite odd at the time and now I find inexplicable. Perhaps they lost a lot of other applications.

There are some things in this article I agree with and many things I don't.

For a start the weird ad-hominem attacks on Mike Wooldridge. Mike took on his leadership role at the ATI in 2022 when it was (I think) a mess. He is not responsible for the mess, I don't know what he's done about it, but to attribute it to him is just flat wrong. And, yes - as part of his mission to communicate about AI (including doing the Christmas lectures) he has described LLMs as prompt completion - which is exactly what they are. The shock was twin fold, that massive computation and data would allow prompt completion as good and useful as it is and that someone would spend $10m on a single training run for 175bn parameter one. These two things show that our understanding of natural language and economics were both radically wrong... Also AI is not a monolithic discipline and Mike is not an NN or NLP researcher, he is a specialist in game theory and multi-agent systems, so this is like criticising a condensed matter physicist for not predicting dark energy. Anyway, take it from me, you've taken aim at the wrong person and it's unpleasant and unfair.

The thing about Deepseek is especially egregious. Of course he hadn't heard of them. Until V2 hardly anyone I know had, they made some interesting models but nothing really significant. V3 changed that. The sponsorship of the CCP was an important part of this change, if the CIA didn't know why should Mike?

Now, moving on from unhelpful personalization of a national issue. From 2015 there was a full on effort to drive interest and activity in deep networks in UK academia. I think my journey was typical of AI people in those days. I was quite negative about Alexnet in 2012, I really thought that there was something silly. I asked an intern about it and got comprehensively schooled in the discussion, so I went and looked at it carefully and rapidly realised I was wrong and they (Hinton and so on) were right. It was just a fact, then people (and me) were scrambling to get GPU's, use GPU's find applications and so on. There were events at the Royal Society, Geoff Hinton and Demis Hassabis were speakers (me as well, but the audience looked very bored for that bit). It was not seen or treated as a curiosity, it was seen as the way of the future - without equivocation. So the idea that it was treated with skepticism is just nonsense. I remember asking Wooldridge about his opinion of neural turing machines (a deepmind paper) in 2014 and he was extremely positive and clear that the work was important. This is just an example, but I was there and I can tell you: UK academia was not skeptical, impressed, excited, interested, but not skeptical.

What do I agree with in the assessment you present and what do I think happened?

You are right that it has failed to create practical outputs. You are right that it has focused in a very silly way on imaginary ethical issues rather than developing useful outputs. Notably, there isn't any reason to make a claim of value for any of these outputs, they haven't made any impact. You are right that it has built a secretariat rather than a capability for the UK.

I did not think that the ATI should act as an admin mechanism for the research councils. For some reason 70 odd admin people were appointed before anything happened. They were all very busy writing policies. I did not think it should act as a recruitment system for the universities either although I did appreciate that the Keck does that for uni's in London and nearby. The Turing had to be a national beast, I thought, so the geographic stickiness of the Keck was not appropriately. Also labs and physical location matter less for compsci. I did not think that the ATI should do independent research, in fact I thought, and think, that that is ridiculous. We have lots of compsci research in the UK. What we have precious little of is transformation of research to practice.

When the ATI was started up it was clear to me after about 30 minutes wandering around the space in the BL and talking to them, that no one involved knew what to do apart from try to get more funding to make it sustainable. I remember a group of professors spending two days in a room wrangling strategic priorities. I was excluded from this process which annoyed the piss out of me, but nevermind, I would probably have had a stroke if I was included. What made me laugh was that there were 20 participants and they produced a list of 20 priorities.

More funding was a pretty difficult objective to argue with and I think that central government had passed a pretty clear message that if the ATI couldn't attract considerable extra funding then it could expect a pretty short lifespan. As above, it was the only issue that anyone could agree on anyway. The problem though, I think, was that the academics who were running it had very little idea of how to engage with industry. I was told that they were interested in collaborations that carried at least £10m funding a year because it wasn't worthwhile to engage with organisations that would put less than this in. There were very few organisations around that were prepared to put £10m with no strings attached and no commitments to anything than funding research in Data Science, Big Data or AI into a brand new institution with no track record. The ATI folks seemed to think that they could just wait in the British Library for sponsors to show up, bringing contracts with them. In fact it wasn't even that they didn't sell the ATI, when I tried to proactively get engagement they were clear that the kind of collaboration in the six figures range that I could stretch my organisation to consider was not of interest at all.

To be fair I suspect that if I had been able to put the collaboration I wanted on the table my organisation would have turned it down anyway, so maybe the ATI were right on that. Anyway there was no viable strategy to get commercial sponsors in the numbers needed both for money and to drive the insitute. Hence, the turn to the academic money mill.

So, fully rebuffed, chastened, and put in a box, but still as thick as mince and oblivious to the undoubted derision swirling about me (or just complete disinterest) I carried on and pushed two ideas, which no one was even slightly interested in. I also think that there was a bloody obvious one that I didn't push because it wasn't my bag that they didn't do as well.

The first idea I had was that the ATI should serve as a bridge between UK academia and UK vital industries. My logic was that the UK lacks national champions in software and hardware and therefore a bridging institution could or should support technology transfer from academia to the NHS, FS, Defence and pharma. To be fair I think that people at the ATI would point at the defence collaborations that you highlight and say that worked out, but in truth I don't really think it has at all.

The second idea was that the ATI should structure activities around the consortium model that MIT was using at the time and I had participated in very successfully. Basically groups at MIT identify a topic and then advertise (through the institutions networks) the opportunity for others to participate. Participation requires a significant fee, but the fee is only a part of the consortium's overall funding and that means that you are buying into a research program that is many times larger than you could fund independently. The consortium then offers a range of ways for members to participate including workshops, courses, meetups, placements and so on. I will be frank, the ATI people I pitched this too looked at me in much the same way that my dog looks at me when I try and get her to play chess, although I am happy that none of them bit me.

The blinding miss is that I think that the startup community in London could have benefited significantly from the ATI facilitating and developing their work - but I am not a startup guy so didn't explore that. There was a lot of entanglement with CognitionX which I just couldn't understand. I don't think my networking autism did me any good in that conversation. Perhaps if I had acted differently I wouldn't have a mortgage now. The banner of the ATI web site still doesn't feature startups or entrepreneurs. I find that shocking (clutches pearls).

Anyway, my fellowship was a total bust and I was quite pissed off about it. I had a relatively young family at the time and I spent quite a lot of hours messing about at the ATI when I could have been messing about in the garden with them. Writing all this down makes me feel a bit better now - but so has being out doing AI in industry for the last ten years and earning some cash while I've been doing it.

What a bloody shame though, it's been a massive miss and I will always regret that I lacked the skills, personality, and gravitas to influence what happened.

I've been involved with Turing for many years and so much about this reflects my experience. Too many of the Programme Directors were academics who were just interested in creating mini-empires for themselves. The Turing was a nice source of funding, outside the usual grant structures, for their own niche activities and agendas. However, the core institute did not help itself either, an internal set up with far too many community and programme managers often doing things on the periphery of the core mission of AI and data science and a leadership too scared to focus the core staff and just letting them do whatever they want. It was a long running joke that the Turing had a bigger administrative machine to run a few hundred researchers than many university departments who were looking after thousands of students and staff.