Introduction

While studying history a decade ago, John Brewer’s The Sinews of Power left an impression on me. Brewer argued that Britain's rise as a global power in the 18th century had little to do with limited government or ancient English liberties. It instead resulted from its development of an efficient "fiscal-military state" capable of effectively raising tax revenue and managing the national debt to fund warfare. This revolutionary state apparatus featured professional bureaucracy, sophisticated financial markets, and a system of long-term public borrowing that allowed Britain to mobilise resources more effectively than its continental rivals, despite its smaller population.

This has stuck in my mind as European governments reckon with a US administration that seems content to abandon its place in the world and engage in the mafia-like extortion of its long-standing allies. We’ve seen European leaders rush to express their solidarity for the embattled Ukrainian government, while governments have pledged to revisit the question of defence spending. European Commissioner Ursula von der Leyen has spoken of freeing up €800 billion for defence investment, although the maths behind this number remains unclear.

But defence is messy. The sinews of power in the 21st century are slightly more complicated than they were in the 18th, but many of the underlying principles are the same. Three hundred years ago, effective defence required good institutions, markets and physical infrastructure. Spending on the military was only one - very important - piece of the puzzle. I’ve written before about Britain’s hollowed out shopfront military; this time, I take a wider European perspective, looking beyond just equipment to cover some of the other sinews. The picture isn’t cheerier.

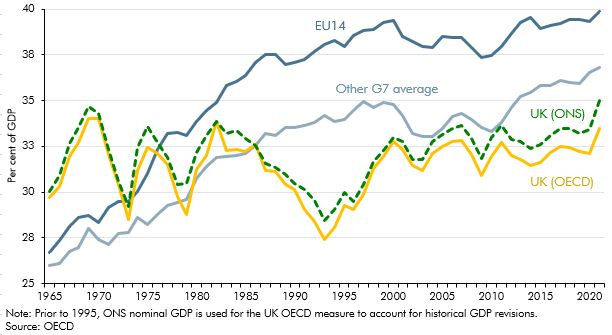

I’m afraid there is no money

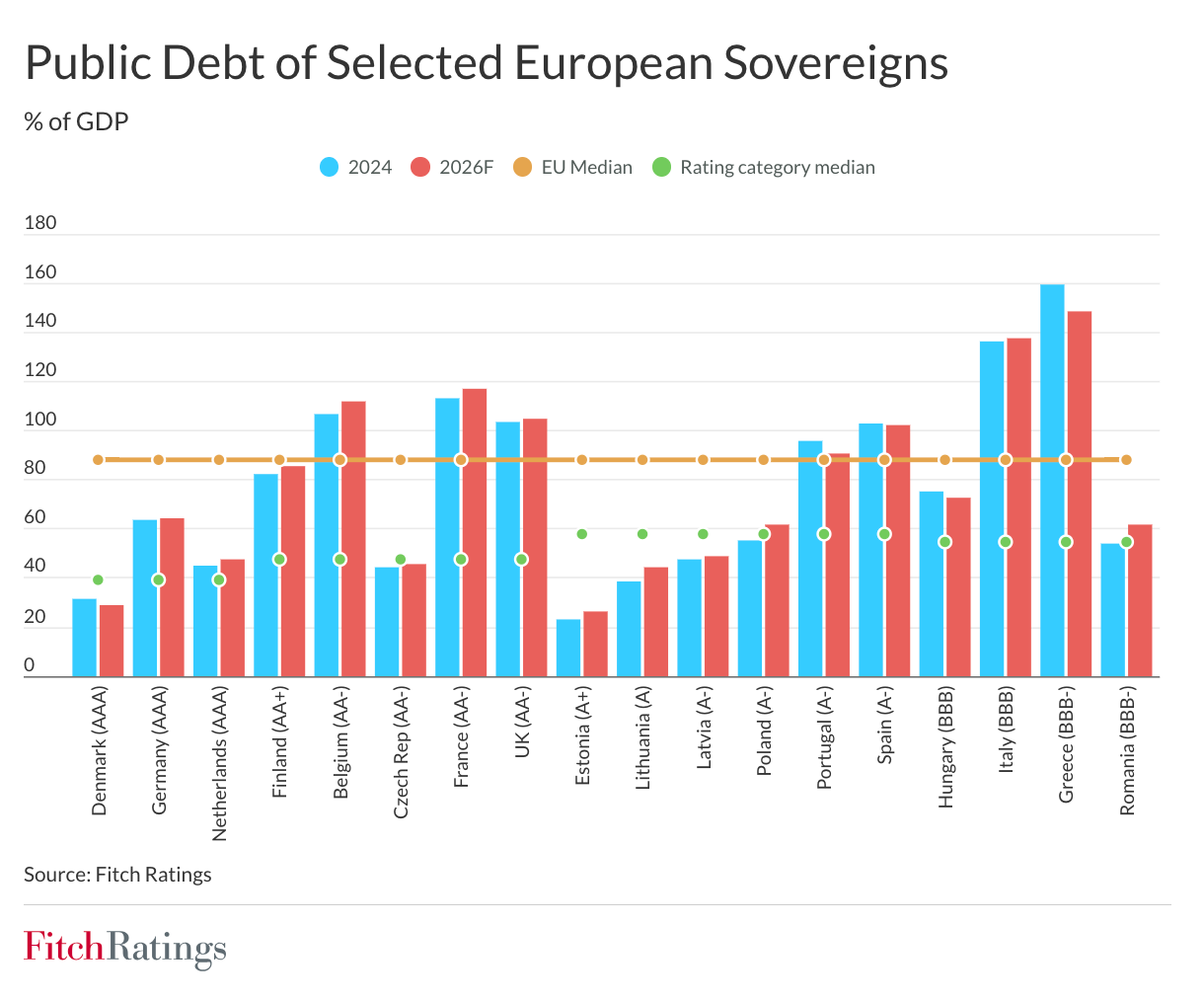

Defence is expensive and many of Europe’s largest economies are broke.

France and the UK, historically been among the world’s biggest spenders on defence, are out of fiscal headroom. Poland, which is comparatively economically healthy, is already ramping up defence spending. The Baltic states can afford to spend a greater share of their GDP on defence (and are already doing so), their smaller economies mean that the money will only stretch so far.

While most NATO members are now set to hit the 2% spending target, the prospect of a significant US pullback means that this is no longer sufficient. Bloomberg Economics has forecast that European governments could face a defence bill of $3.1 trillion over the next 10 years. This assumes European nations will move towards spending 3.5% of GDP on defence and that they will have to cover the cost of maintaining a Ukraine peace-keeping force and post-war Ukrainian economic reconstruction.

It could be that these Bloomberg spending figures are on the conservative side. These numbers might be enough for Europe to bulk up its armed forces and equip them, but there are certain capabilities that European militaries have essentially never provided for themselves. For example, European states have never fielded an independent ballistic missile defence capability. They lack the necessary radar equipment, while the SM-3 interceptors we currently rely on for upper-tier missile defence sit on US Aegis destroyers. Andrius Kubiliu, the European Commissioner for Defence and Space has previously said that a missile shield could cost Europe €500 billion.

This isn’t the only area of dependence. European governments are also dependent on US multistatic sonobuoys to listen out for submarines and rely heavily on US nuclear attack submarines to trail Russian submarines. The loss of this capability would leave crucial undersea cables undefended.

Is there a magic money tree?

So, how are European governments going to come anywhere close to paying for this?

Conventional measures like reallocating spending or hiking taxes will make up some of the gap, but this will prove politically difficult beyond a certain point. The UK might be able to increase defence spending from 2.3% of GDP to 2.5% in 2027 via the relatively politically painless step of cutting international aid spending, but finding further money will prove harder. France’s government collapsed in January of this year after proposing cuts to social security after ratings agencies had started to downgrade French debt.

The German government is attempting to repeat its 2022 manoeuvre of suspending its notorious constitutional ‘debt brake’, which limits the federal government’s structural deficit to 0.35% of GDP, to facilitate greater defence and infrastructure spending. This is running into difficulties, as the Greens are threatening to block the move in an attempt to extort more money for environmental causes. A higher spending, higher borrowing German economy might well be more dynamic long-term, but this is already having implications for the borrowing costs. Yields on German bonds have spiked following their biggest sell-off since 1990.

This has implications for other European countries.

German bonds were historically considered some of the safest sovereign debt in Europe, to the point where it carried a negative yield at times. This means that investors were paying to lend the German government money (while counterintuitive, this can make sense). If bond investors can now expect a 3% yield on German bonds, they will expect higher returns from riskier countries. This has already started to push up French and Italian borrowing costs.

With the political mood against spending cuts, are tax rises on the agenda? With the tax burden in many European governments already at their highest in decades, large-scale tax rises will prove difficult. That said, some European governments are exploring squeezing their wealthiest citizens further.

The only realistic path forward is likely to involve a heavy debt component.

As our French and German examples show us, markets aren’t wild about individual European nations borrowing ever more money, the EU’s broad shoulders may yet play a useful role.

There has already been talk of the EU loosening some of its rules on government debt and shuffling money between various bank accounts, but the most controversial proposal is a plan to borrow up €150 billion for defence.

The EU has issued debt for a while, but has scaled this into the hundreds of billions in recent years. We saw this in the €650 billion Covid-era Recovery and Resilience Fund, as well as its Ukraine Facility.

Despite relatively high debt-to-GDP ratios in many individual European states, EU bonds have so far proved reasonably popular with investors. Some EU bond issues have been as much as 11x oversubscribed. These bonds benefit from the backing of multiple governments and the support of strong EU institutions and governance frameworks. Every ratings agency except S&P gives the EU an AAA rating.

Euro bonds also provide investors some helpful diversification, giving them a high-quality euro-denominated asset, without tying them to a single country’s risk profile. They also offer the “safe haven” status of the German Bund (issued by the EU’s only major AAA-rated economy), without its (until pretty recently…) measly yields.

If this is such a no-brainer, why hasn’t the EU already done it?

There are three blockers - the first of which can probably be (sort of) ignored, while the latter two are solvable with concerted political will.

Firstly, the macro backdrop for bonds is less favourable than it was in 2020-2021. Interest rates are higher, there’s been a flood of big government debt issues in the past year, meaning that borrowing costs are going up. That said, there’s early evidence of institutional investors expressing interest - it’s just likely to come at a steeper price.

Secondly, we should expect a blazing row about who does and doesn’t want to participate. In short, the EU is split into factions between the enthusiasts (e.g. countries with borders near Russia), the sceptics who would rather existing money was moved around in the first instance (e.g. The Netherlands, Sweden), and the undecideds (e.g. Denmark, Germany, Austria).

As a result, we may end up seeing a vehicle that operates outside the standard EU treaty framework, potentially via an intergovernmental agreement between participating countries. This would be unchartered territory, but might have the advantage of allowing the UK to participate. The more countries that join, the better. If the coalition of the willing ends up being very small, “I can’t believe it’s not French debt” is unlikely to set investors’ hearts racing.

Thirdly, we should expect a tussle over how the money is spent. France will lobby hard for the money only to be allocated to European defence contractors (I wonder why…), while other nations will want more flexibility.

New money, legacy commitments

Once the spending taps are turned on, should we expect to see European rearmament accelerate drastically?

Up to a point. Unfortunately, defence doesn’t start from a blank slate.

For example, France did hike defence spending last year, with the country preparing to spend 40% more between 2024 and 2030 than it did between 2019 and 2025. While this sounds like a lot, it goes less far than you’d think. This is for two reasons.

Firstly, the more sophisticated your military, the more existing commitments need funding. In France’s case, 13% of the new budget will immediately be consumed by the nuclear deterrent, where carrier platforms, missiles, and submarines all need upgrading. It’s not an altogether different picture in the UK, where the government’s decision to prioritise the punctual upgrade of the nuclear deterrent will eat up a meaningful proportion of the money allocated to the Ministry of Defence’s equipment plan until 2033.

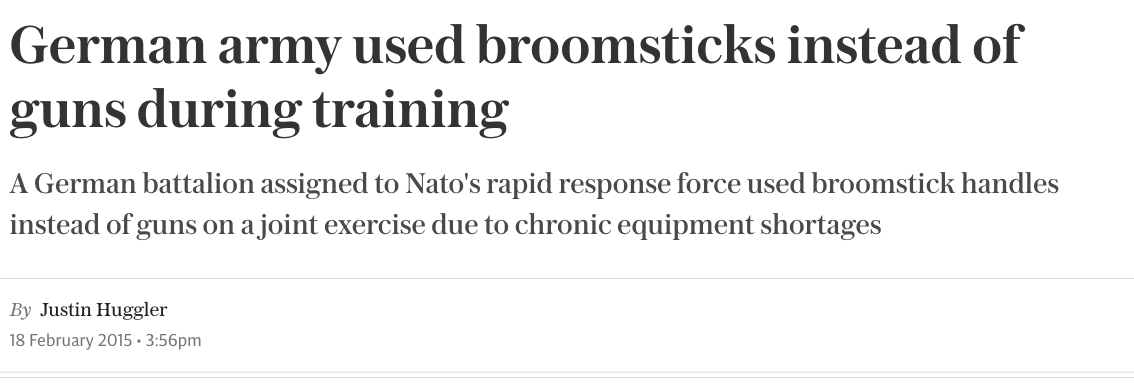

Secondly, during the post-Cold War lean years of European defence spending, governments routinely deferred modernisation programmes and stripped out resilience, creating significant legacy debts. This means new money often has to be spent fixing existing equipment or restoring empty stockpiles.

For stretches of Operation Barkhane, France’s counter-insurgency operation in Sahel, less than half of the country’s military helicopter fleet was deployable, while Tiger attack helicopter availability dropped as low as 25%. Meanwhile, since 2011, six out of the country’s 20 ammunition depots have been closed, leaving the armed forces with the stocks to last a few weeks in a combat against a peer nation.

France is at the better end. In 2015, equipment shortages forced German soldiers to use broomsticks painted black instead of guns during a NATO exercise.

Could we all just be more like Poland? Many defence enthusiasts I know look at the country enviously, as it prepares to increase defence spending to 4.7% of GDP this year. Poland has the largest NATO land army in Europe and has won plaudits for its efficient off-the-shelf procurement of South Korean tanks, as it transitions away from old Soviet equipment.

There’s a lot to commend about Poland’s sense of urgency, but the picture’s a little bit more complicated than it appears on the surface. Much of its budget goes unspent, there’s a shortage of experienced personnel (thanks to a combination of recruitment challenges and politically-motivated purges by the previous government), procurement is more chaotic than the headline orders make it appear, and there’s a shortage of specialists who can help implement new systems. In short, building an effective military and accompanying culture takes time. More money helps, but it can’t shortcut everything.

A stretched industrial base

But let’s say we find the money to resolve all the legacy dents and then acquire some new capabilities, is that it?

Not quite.

You then need to produce and buy the equipment. Most defence contractors don’t have large stockpiles of spare munitions sitting around, especially the kind that would be useful for a confrontation with a peer adversary. Margins in defence are slim, as governments tend to cap profit levels. This means manufacturers are incentivised to run just-in-time operations optimised to the needs of their biggest customers - rather than maintain stockpiles or spare capacity.

This is even the case in a country like the US, where defence spending has remained reasonably high after the Cold War. Since the turn of the millennium, the US has been overwhelmingly focused on counterinsurgency operations and asymmetric warfare.

For obvious reasons, these operations tend to rely more on light, mobile equipment and precision munitions. Considering the Taliban and al-Qaeda were unlikely to ever outgun their American opponents, there was also little need to maintain much idle capacity. As a result, the US can reportedly only produce 1/9th of the shells a month that it could in 1995. A recent Taiwan wargaming exercise found that the US would exhaust its entire global inventory of long-range anti-ship missiles within the first week of the conflict.

While President Trump is insisting that European governments are obliged to buy more American arms, US manufacturers are already struggling to meet existing orders from foreign customers. This means there is little option but for European countries to restore domestic arms production.

Unfortunately, this is far from easy.

France again gives us a helpful illustration. A once globally significant defence industry has been allowed to atrophy due to lack of domestic demand and cheaper competition from countries like South Korea. While sales of the Rafale fighter keep French industry relevant, there is little domestic production of infantry equipment. The only notable exceptions are lightly armoured vehicles like the Jaguar and Griffon, which are designed for the kinds of asymmetric conflicts France has been fighting in west Africa.

The Leclerc, France’s main battle tank, is no longer produced at all, after it proved an export flop. The Main Ground Combat System - a Franco-German project to replace the two countries’ battle tanks - looks unlikely to be operational before the mid-to-late 2030s.

To compensate for these weaknesses in the country’s defence-industrial base, the French government is exploring whether car manufacturers can turn over some of their factories to the production of kamikaze drones.

Rheinmetall, Germany’s biggest arms producer, has won plaudits for its energetic programme of expansion - building or acquiring facilities across Europe. This capacity will be very useful … eventually. Building and equipping a new factory for heavy industrial production is a slow process, especially if your main customer moves slowly. Even in the face of the Ukraine war, Germany was slow to place new orders. The German armed forces took until July 2024 to order a batch of new Leopard 2 tanks, which will mean delivery in 2030 at the earliest.

Mass and infrastructure

Once the new equipment arrives, there’s the additional task of operating and transporting it. The two crucial components for this are mass and infrastructure. Europe lacks both.

Mass is critical - not just for fighting, but because of defence’s growing complexity. In a world of increasingly advanced weapons systems, aircraft, and vehicles, a long chain of people are needed to manage logistics and technical support.

The proportion of combat soldiers versus support, sometimes called the “tooth-to-tail ratio”, has grown from about 1:4.3 during World War II to closer to 1:10 today. This ratio was one (although not the most decisive) factor in the rapid collapse of Afghan security forces during the 2021 US withdrawal.

The Afghan military depended heavily on US contractors for maintenance, repair, and logistics. Once the US supply chains were dismantled, it was impossible to source spare parts. This, for example, meant that the Afghan Air Force was essentially inoperable. European governments risk being in exactly the same position with many critical capabilities; this is a much more concrete concern than the US flipping a hypothetical software kill switch.

There was a long-standing belief (or rather, hope), that new technology would reduce the requirement for mass. However, the Ukraine conflict has clearly demonstrated that technological advances in conflicts between peer nations are usually temporary. While Ukraine may have surprised Russia in the opening phase of the war with its use of drones, the Russian military quickly learnt to respond in kind. Mass quickly asserted its importance.

This is why a recent UK House of Lords report on UK military readiness concluded that “the evidence we heard points to the current size of the British Army being inadequate … we are concerned that the Army cannot, as currently constituted, make the expected troop contribution to NATO”. Meanwhile, Michael Shurkin, a long-standing analyst of the French military, argued in a report that despite the country’s military “being indisputably the most capable in Western Europe”, it “lacked the depth and the mass to do anything on a large scale for any length of time before it simply ran out of stuff”.

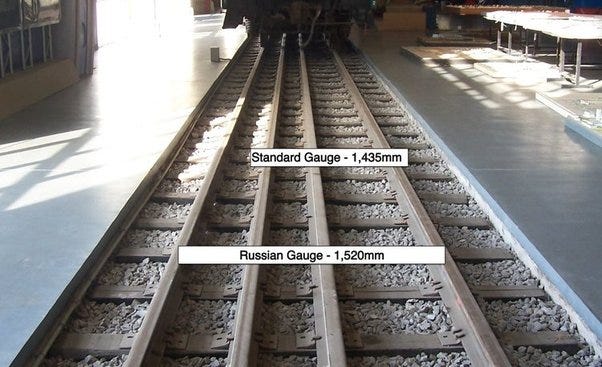

Once they have the equipment and the support staff in place, militaries then need to be able to move everything around. Crucially, you need good railways, roads, and bridges.

Germany, traditionally Europe’s key hub for military logistics, has underinvested in infrastructure, meaning it increasingly struggles to handle heavy infrastructure. There’s also a shortage of railway wagons capable of moving military equipment.

Once equipment gets through Germany, it runs into another problem. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia’s railway tracks were built with a wider Russian gauge, leaving the Baltic nation better connected to their prime adversary than their allies.

RailBaltica, the plan to connect Baltic capitals with Warsaw via European standard-gauge track won’t be completed before 2030 at the earliest.

So, is all hope lost

After this litany of woe, it might be natural to counsel despair in the face of overwhelming odds.

While the kind of Ukrainian victory people envisaged in the summer of 2023 is clearly off the table now, the Ukrainians aren’t up against an invincible war machine. As former Ukrainian defence minister Andriy Zagorodnyuk put it in a recent article:

At the moment, Russia’s troops are exhausted, its defence production is struggling to keep pace with battlefield losses, and its unmanned weapon systems are, despite great effort on Moscow’s part, struggling to prevail over those of Ukraine. Unexploded drones and missiles recovered from the battlefield are mostly of very recent manufacture, indicating that Russia has depleted much of its stockpile and is deploying new weapons as soon as they become available. Meanwhile, even with Russia’s large population (and soldiers from North Korea), recruitment levels are failing to meet demand, and the high casualty rate leaves little time for adequate training of new troops.

Additional European support could make a difference in strengthening the Ukrainians’ hand, so they can secure a better outcome.

Beyond the immediate conflict, there is a bigger political argument to be won. As we established above, good defence requires long-term investment and planning. That means spending will need to be maintained well above 2.5% of GDP for years after any cease fire. The temptation to raid defence budgets to buy-off increasingly weary electorates, who might otherwise be tempted to vote for populists, needs to be resisted at all costs.

These battles are winnable. At the end of the day, Europe’s most immediate adversary is a country with a commodity-dependent economy smaller than that of Italy, a declining population, increasing dependence on China, and diminishing influence in much of the world. This doesn’t have to be David versus Goliath (although famously, David came out pretty well in that match up). But if European countries want to defend the values they so often champion, they’ll have to pay a price.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer, my dentist, or anyone else. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Image credit: Leclerc battle tank, Daniel Steger (Lausanne, Switzerland), CC BY-SA 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

This is absolutely great.