Lessons from the UK's dumbest trade war

How the Royal Navy went three rounds with the Icelandic Coast Guard and lost

In September 1958, the first shots were fired in anger in the North Atlantic since World War II. This wasn’t a tense Cold War stand-off between the US and the USSR. Instead, it was an Icelandic patrol boat firing a blank at a British trawler in the first of three ‘Cod Wars’ between the two countries.

Between 1958-61, 1972-73, and 1975-76, the UK and Iceland engaged in a series of confrontations over fishing rights. In each one of these, the UK, despite its overwhelming military and geopolitical heft, was beaten decisively.

The Cod Wars were big news at the time in both the UK and Iceland, but are no longer discussed frequently outside the context of fisheries policy. These sorts of discrete asymmetric conflicts, however, interest me. They showcase how countries view their standing in the world, their strategic assumptions, and the limitations of doctrine. The Cod Wars specifically, however, also embody a series of common flaws in the UK approach to a range of policy and strategy questions in 2025. In this piece, as a welcome break from UK metascience, I retell the story and cover some of the lessons.

What were the Cod Wars?

The prequel

From the 1890s onward, British trawlers, primarily from Hull and Grimsby, began to fish off the coast of Iceland. This distant fishing trade became central to the economy of a number of coastal towns over the ensuing decades.

In this era, as the undisputed master of the high seas, Britain set the commonly accepted standard that territorial waters extended three miles beyond a country’s shoreline. The UK saw this limit as critical. It allowed Royal Navy vessels to sail close to foreign shores for military and intelligence operations and enabled the unrestricted sea lanes that facilitated British trade. It was the position of the British government for the nineteenth and the early twentieth century that it would fight a war to uphold the principle.

Danish-ruled Iceland attempted to extend this limit to four miles at the end of the 19th century in order to preserve more of its fish stocks for its own citizens. In response, Royal Navy ships paid Reykjavik two friendly visits over 1896-97. This led to the Danes reconsidering and formalising the three-mile limit in a 1901 treaty. This was the status quo for the next five decades.

In 1951, after the International Court of Justice ruled in Norway’s favour on a four-mile limit, Iceland tried again. British trawlermen and their unions were incensed and the British government tacitly supported their decision to prevent Icelandic fish from being unloaded at UK ports. The blow to Iceland was softened by the US and its allies, along with the USSR, stepping in to buy Icelandic fish. Following a 1956 negotiation with the Organization for European Economic Cooperation, the UK reluctantly backed down and accepted the four-mile limit.

The peace didn’t hold for long. In September 1958, Iceland unilaterally expanded its limit to 12 miles, following a series of inconclusive negotiations. The Icelanders declared that any British trawler sailing within these limits would be detained. The UK government dispatched the Royal Navy to escort its fishermen. On paper, this should have been a rout. While diminished from its imperial peak, the UK still wielded one of the world’s foremost navies, while Iceland had a handful of largely unarmed patrol boats. But it was not to be.

It’s war

On 2 September, the first skirmishes broke out. Grimsby trawler Northern Foam was intercepted by two Icelandic patrol boats and signalled to British frigate HMS Eastbourne for assistance. Using a loudhailer, Commodore Anderson for the UK attempted to defuse the situation, calling out to his Icelandic counterpart Captain Kristófersson: “Kris, Kris, this is bloody daft! I’m coming over to talk to you”. After a friendly debate about the rights and wrongs of the matter, the Eastbourne brought the Icelandic raiding party aboard ‘as guests’. An attempt to detain another Grimsby vessel was repelled by the crew, wielding boat hooks, poles, and an axe.

Andrew Gilchrist, the British Ambassador to Iceland, combined an understanding of Iceland’s strength of feeling with irritation at the manner in which they were treating British sailors. At noon on 2 September, after the first skirmishes had been reported on the radio, a crowd of a few hundred protesters, primarily made up of drunken teenagers, had gathered outside his residence. Gilchrist had invited a group of foreign journalists to observe the hostility of the Icelanders first-hand. After the crowd failed to do more than chant a few slogans, Gilchrist blared ‘The Barren Rocks of Aden’, a jaunty pipes and drum military march, on the gramophone towards the crowd. Amid cries of ‘Vikings never give up’, members of the crowd stormed the garden, smashing glass.

Things would only get worse. Unwilling to take Britain’s ‘victory’ on the first day of the Cod Wars lying down, the Icelanders began to fight back. Heavily-plated Icelandic patrol boats began to ram both British trawlers and their naval escorts. A number of tense stand-offs ensued, where Icelandic patrol boats would fire blanks at trawlers. The trawlers would ignore them and the navy would show up and threaten to open fire. Tempers became heated, with one naval officer shouting at an Icelandic patrol boat over the loudhailer, “if you try to ram me, I will blow you out of the water”.

Anderson warned the Admiralty, “I appreciate the political problems but urge a face saving interim solution to be found quickly for both countries if only to save the needless loss of life.” On one occasion, a trawler and an Icelandic gunboat pelted each other with dried cod and rotten potatoes.

While Britain overwhelmingly outgunned the Icelanders - it suffered from two weaknesses.

Firstly, the optics of the Royal Navy showing up to push around a tiny, newly-independent country played dreadfully. While other NATO nations and international courts believed Iceland to be in the wrong, there was widespread sympathy for the Icelandic underdog, even among the British public. Had members of the Icelandic coast guard been killed in clashes, the mood could well have turned poisonous.

Secondly, while the Navy was largely successful in allowing British trawlers to continue fishing - it was a costly affair. The Icelandic patrol boats were operating in the immediate vicinity of their home base, while British frigates had a journey of more than a thousand miles back to port. Despite their superior firepower, British frigates were lightly armoured vessels primarily used to chase Soviet submarines, making them vulnerable to Icelandic ramming attacks.

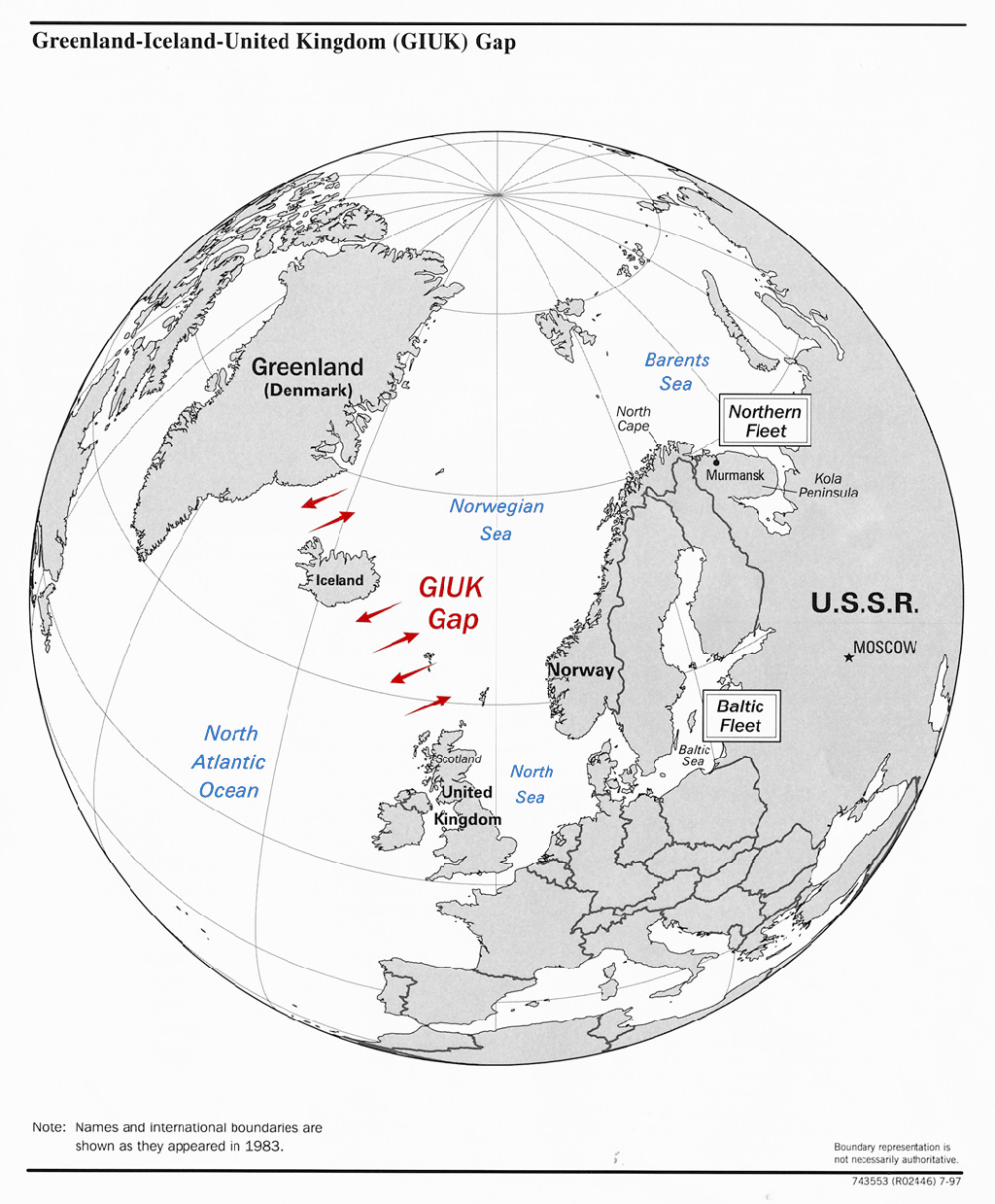

Mounting costs and rising international opprobrium might have been enough to help Iceland win, but it had a trump card. Two years after joining NATO in 1949, Iceland had allowed the US to establish a military base near Keflavik, on the southwestern tip of the island. This base served as a crucial node in American nuclear strategy, variously acting as a base for long-range bombers and a listening post for submarines. Soviet nuclear submarines had to pass through relatively shallow straits between the north coast of Scotland and Greenland on their way home, making Keflavik the perfect spot for sonar installations to monitor them.

In all three of the Cod Wars, Iceland threatened to leave NATO and cancel its bilateral defence agreement with the US. In the Third Cod War, it went as far as breaking off diplomatic relations with the UK.

These threats were given credence by UK and US fears about communist influence in Iceland. The two countries had (wrongly) suspected that anti-British sentiment had been whipped up by the far-left, ignoring indications that it was an issue of cross-party consensus. Iceland’s fish sales to the USSR, combined with the growing Soviet embassy in Reykjavik, which had a staff contingent double the size of Washington’s representation, did little to allay these fears.

In each one of the Cod Wars, Iceland’s suggestion that it might leave NATO and close the airbase helped prompt a British climbdown. There isn’t clear evidence that the US instructed the UK to back down in the face of this threat; it’s perhaps more damaging for British pride that they didn’t even need to.

The first Cod War ended with total British capitulation in 1961, with the UK accepting the 12 mile limit in exchange for some interim fishing rights.

The second and third Cod Wars followed somewhat similar trajectories, only with greater vehemence.

In the second Cod War of 1972-73, the Icelandic coast guard began to deploy net cutting devices, which increasingly made it impossible for unescorted British trawlers to fish.

To avoid a repeat of the first Cod War, the UK initially used unarmed tugboats to interpose themselves between the trawlers and the Icelandic patrol vessels. This idea had been floated half-jokingly in a meeting at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food only to be subsequently adopted as policy, with the backing of the Ministry of Defence and the Foreign Office. In a bureaucratic confusion over shipping registrations, Statesman, the first such vessel to be deployed, sailed under a Liberian flag.

Unsurprisingly, this did not get the job done and the Navy was summoned back. This phase of the conflict was less gentlemanly. There were mass protests in Reykjavik, live rounds blew a hole in the side of a British trawler, while one member of the Icelandic coast guard was killed in a ramming incident, when water coated the electrical equipment he was operating.

After NATO brokered talks, the Navy left Icelandic waters, while British trawlers played Rule Britannia and The Party’s Over on their radios. The UK accepted Iceland’s 50 mile limit.

The third and final Cod War followed a similar trajectory to the second, only with Iceland pushing for a 200 mile limit. This saw the most shots fired and the greatest number of ramming attacks, with 15 British frigates damaged. HMS Eastbourne, the vessel from the UK’s triumphant first skirmish in 1958, incurred such bad structural damage that it was never judged seaworthy again.

However, the UK was on much weaker legal footing by 1975. The ongoing United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) was already moving toward recognising 200-mile exclusive economic zones, while expansive limits were increasingly becoming a global norm. In June 1976, after a mere seven months, the UK capitulated.

What went wrong?

One of the most striking features of the Cod Wars was their similarity. Over a span of 18 years, the British government repeatedly deployed the same set of tactics to no avail. As former ambassador to Iceland Andrew Gilchrist put it:

“If some reasonable degree of excuse and explanation can be offered for the British government’s actions in … 1958, surely it passes comprehension that when confronted by an identical problem in 1972 and 1975, the government should have had recourse to the same measures which had proved so ineffective and counterproductive on the earlier occasion.”

Britain’s failure to change its approach resulted in worse outcomes. Before the second Cod War, the UK rejected Icelandic proposals that were more generous than the settlement it obtained post-conflict. Meanwhile, Iceland actually hardened its negotiating position over the course of the third Cod War, as growing violence soured domestic opinion.

So how did the UK settle on the same set of failed policies each time?

Failure of imagination

A significant driver was a failure to understand the other side. A 1963 account of the first Cod War observed that there was little interest from outsiders in understanding the Icelanders on their own terms:

“Visitors tend to be interested mainly in unusual characteristics (geysers, glaciers, boiled sheeps’ heads, and the like) or in topics directly relevant to their own country. Americans, for example, often write about the Keflavik base or about the threat posed by Communist strength in politics and the labor movement.”

While fishing was important for the UK economy, it was existential for Iceland. Between World War II and the first Cod War, fish had accounted for more than 87% of Iceland’s exports, rising to 97% in some years. It did not occur to planners in London that simply ramping up the display of force, as they did in the second and third Cod Wars, would not scare their adversaries into submission.

Iceland had secured its independence from Denmark in 1944 and for many Icelanders, the Cod Wars were the next front in their struggle for freedom. They had secured their political independence, but not sovereignty over the country’s most important resource. During the second Cod War, many Icelanders would put bumper stickers on their cars, depicting the map of Iceland encircled by a chain.

This mood was apparent to British officials in Reykjavik. As one noted in 1959:

“The Government] had failed dismally to understand the Icelandic psychology and make the necessary allowances for the sensitivity of a very small country which had so recently gained its independence. … [they] might have applied some of the lessons they had learned the hard way in Ireland, with which there were striking historical and temperamental similarities”.

This psychological failing was clear when Ólafur Thor, Iceland’s industries and fisheries minister visited London in 1952 during the prelude to the first Cod War. As a serving minister and three-time prime minister of a NATO ally, he was affronted that not a single minister found time in their diary to meet with him.

This failure of empathy was fused with a lack of institutional knowledge. Iceland’s coalition politics were little understood in the corridors of power in London. Different parties would jockey for position, attempting to outflank each other. Amid this confusing picture, the UK defaulted to assuming the worst, believing Iceland’s true intention was to exclude all foreign fishermen from its waters.

Fear of decline

In 1849, a mob in Athens attacked the house of David Pacifico, a British subject and former Portuguese consul-general to Greece. Allegedly, the police stood by and failed to break up the crowd, which included the sons of a government minister.

In response, Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston sent the Royal Navy to blockade Greek ports until compensation was paid. Defending his actions in a debate in the House of Lords, Palmerston said:

"As the Roman, in days of old, held himself free from indignity, when he could say, Civis Romanus sum, so also a British subject, in whatever land he may be, shall feel confident that the watchful eye and the strong arm of England will protect him from injustice and wrong."

This was the golden age of ‘gunboat diplomacy’: a short display of naval power to achieve diplomatic goals. The British Empire, wielding the world’s powerful navy, were the undisputed masters of this art.

100 years later and economically devastated by two world wars, Britannia was receding on all fronts. The 1956 Suez Crisis, where international outcry forced the UK and France to withdraw from an Israeli operation to topple the Egyptian president, had cemented the notion that the UK was incapable of pursuing an independent foreign policy. A year after the fiasco, the defence budget was cut by 10% and Minister of Defence Duncan Sandys came close to scrapping the UK’s entire contingent of aircraft carriers.

As a result, successive UK governments were acutely sensitive to anything that could be portrayed as another symbol of British decline. Being pushed around by a demilitarised country of 200,000 people was one such example.

The military felt this acutely too. In the run up to the third Cod War, the Navy was facing the prospect of severe budget cuts. The aggressiveness of their response was in part a product of its leadership attempting to showcase the service’s usefulness.

Fear of decline blinded decision-makers to how the Cold War context and NATO had changed the game. In this new world, the naval threat was ultimately a paper tiger. The UK could never really escalate beyond firing warning shots without opening fire on an ally. Meanwhile, the UK’s weakening economy could not support a potentially endless naval commitment. If a more determined Iceland simply chose to press on, what was the escalation?

Stakeholderism

Finally, the UK government was pushed around by a very important stakeholder: the fishing industry. The industry had felt let down by the UK’s acceptance of the four-mile limit in 1956 and pressed hard for the government to take a tougher line.

In the run-up to the first Cod War, the Hull Daily Mail and other media allies of the trawlermen compared Iceland to Egypt under Colonel Nasser, drawing a parallel between his nationalisation of the Suez Canal and the Icelanders’ approach to fishing limits.

In 1972, the Deepsea Fishing Industry Committee labelled Icelandic actions ‘piracy’ and lobbied hard for protection. If the Royal Navy did not accompany them, British trawlermen threatened to stop sailing to Iceland altogether. This would have amounted to de facto recognition of Iceland’s new 50-mile limit - something the government was keen to avoid. Austen Laing, Director-General of the British Trawlermen’s Federation, warned that 100,000 jobs were at stake.

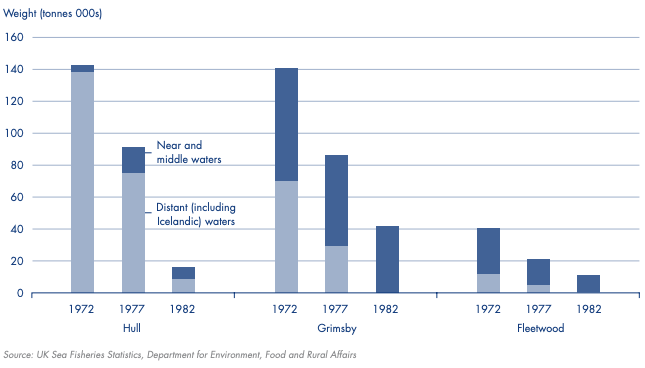

As is so often the case, the stakeholders did have a point. The final settlement in the Cod Wars was a significant contributor to the decline of the UK’s distant fishing industry, with the impact disproportionately felt in a small handful of towns. In the 2000s, after a long campaign, the government ended up making compensation payments to over 5,000 former trawlermen for the damage done to their livelihoods. The payments, which averaged at £9,700, were roundly condemned for their stinginess.

Stakeholders are often expert in identifying their challenges, but less good at policy design. By pushing the government to adopt a more belligerent stance, the industry arguably hastened its own demise.

Closing thoughts

The drivers of the three Cod Wars were unique, but the flaws they showcased in Whitehall and Westminster persist to this day. Stakeholders have held successive governments hostage over a range of policy areas, whether it’s housing, energy, or science and technology. Meanwhile, the UK’s defence budget has been so cannibalised by vanity projects and misadventure that it would struggle to deploy three or four ships to Iceland, let alone the dozens employed at the heights of the second Cod War.

While the UK had limited leverage in its scrap with Iceland, it is currently, somewhat inexplicably, being beaten up by another motivated island nation on the world stage. In its negotiations with Mauritius over the future of the Chagos Islands, the UK has made unilateral concession after unilateral concession while being in a seemingly stronger position. Iceland, after all, could ram British frigates. Instead of fearing decline irrationally, we appear to have pivoted to embracing it.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views only. They are not the views of my employer, the Icelandic coast guard, or any cod in distant waters. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

A note on sources:

This piece is lighter on links than usual, because I relied heavily on books and journal articles. This is a free Substack, not a work of academic history, so I haven’t footnoted every page reference in the interests of readability. My main sources were:

Morris Davis, Iceland extends its fisheries limits (Oslo, 1963)

Jeffrey A Hart, The Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1972-1973: a case study of a fishery dispute (Princeton, 1976)

Jon Th. Thór, ‘The extension of Iceland's fishing limits in 1952 and the British reaction’, Scandinavian Journal of History (1992) DOI: 10.1080/03468759208579227

Gudni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, ‘How ‘cod war’ came: the origins of the Anglo-Icelandic fisheries dispute, 1958-61’, Historical Research (2004) DOIL: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.2004.00222.x

Gudni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, Troubled Waters. Cod War, Fishing Disputes, and Britain's Fight for the Freedom of the High Seas, 1948-1964, PhD thesis (2004), https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/1834

Sverrir Steinsson, ‘The Cod Wars: a re-analysis’, European Security (2016), DOI: 10.1080/09662839.2016.1160376

Thought this was stellar.

Really interesting piece, thanks. But I don't understand the parallels drawn to the Chagos Islands. The principle at stake in Chagos is different, one of decolinization. Much different to a turf war over access to waters for economic reasons.