Introduction

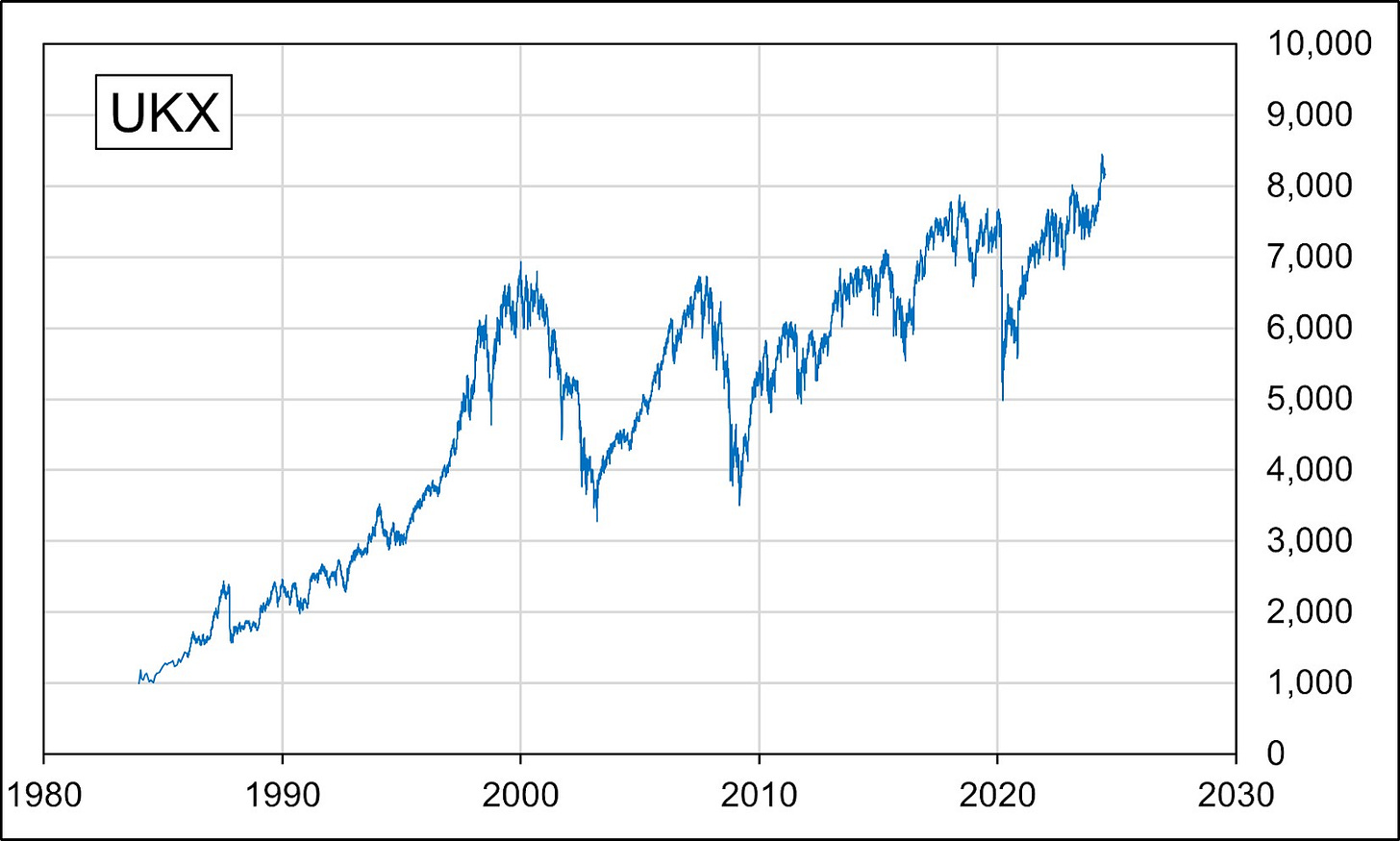

It’s been a bad few years for the London Stock Exchange (LSE). Over the past 5 years, the FTSE has climbed by a distinctly anaemic 15% , while the US S&P 500 has surged by over 90%. Just Eat Takeaway recently announced that it was delisting, the potential IPO of controversial online fashion retailer Shein led to the UK being dubbed the ‘market of last resort’, while the organisation that runs the exchange is widely seen as distracted and focused on other ventures.

There’s a sense of big opportunities being missed or lost. Deliveroo’s 2021 IPO was one of the worst in LSE history. London-listed Darktrace was snapped up by US private equity. Meanwhile, last weekend, London-based asset manager Nick Train said that Arm’s decision to sell to Softbank and delist “objectively was a mistake” and that it could now be one of the top 5 companies on the LSE.

I find the LSE discourse interesting, because I think it’s a good example of how policy discussions get mangled when a bunch of loosely connected issues are blurred together - either by vested interests or policymakers who, bluntly, don’t understand the mechanics. There are legitimate debates to be had around Britain’s poor recent record in large company creation, but the sound and fury over the LSE is largely a distraction.

This week, I run through why we should probably worry less about the movements of the FTSE and take a more realistic view of the prospects for big company creation in the UK.

People may just not know what an exchange is

One of the things that jumped out at me when reading historic coverage of the LSE is that some people may simply not know what listing a company on an exchange does and doesn’t entail.

To give a prominent example, the original Arm sale and decision to list in New York was pretty unpopular. One of the concerns raised was around sovereignty and national security - with a number of Conservative MPs leading the charge. After all, the company’s CPU core design sits in 90% of the world’s mobile phones. For example, Anthony Browne, then the Conservative MP for Cambridge South, said:

“Arm is a leading British technology company of national strategic importance and a major local employer. If it is floated on the stock market, it should do so in London rather than New York or elsewhere to ensure its interests and those of its investors are aligned with our national interest. Ownership matters – particularly of such strategically important companies.”

This is an odd argument for a couple of reasons. For a start, Softbank was only listing a minority stake in Arm. So its IPO venue would make no difference to who controlled the company.

More importantly - where a company's shares trade has limited bearing on who can own them or how the company operates. Countries like Vietnam or India have some restrictions about foreign ownership, but western capital markets are generally open. It’s usually easy for investors from anywhere to buy shares regardless of which exchange they’re on.

It’s not just ownership - where a company lists has minimal consequences for where a company employs people, where its tax revenue goes, strategic decision-making, or regulatory oversight.

If you want to upset some newspapers, you could even argue that by providing UK-based companies with access to deeper US capital markets that we’re advancing our national interests.

Atlas shrugged?

If we’re not worried about the impact of a declining LSE on national security, tax, or employment - should we be worried about its impact on financial services, given the sector’s importance to the UK economy?

In short, no.

The decline of the LSE isn’t great if you’re a tier 2/3 UK investment bank providing services to mid-cap companies or an asset manager with a predominantly UK mandate.

These may be noble professions, but they’re not what the City is built on. While the panic about technology stocks grabs headlines, it’s largely irrelevant for the wider UK financial services industry.

UK asset managers may manage £13 trillion, but much of this is for overseas clients, and 70% of the shares they manage are listed on foreign exchanges.

Many of London’s real areas of leadership are completely detached from the LSE. For example, the city has a 46% share of the over the counter interest rate derivatives market, hosting $2.6 trillion of transactions a day. London is also responsible for $3.8 trillion a day in forex, twice as much as New York.

It’s not hard to see why. London is perfectly positioned for traders who need to straddle Asian and US market hours.

London has the largest speciality insurance market via Lloyd’s of London, while UK-based insurers manage £1.8 trillion in investment.

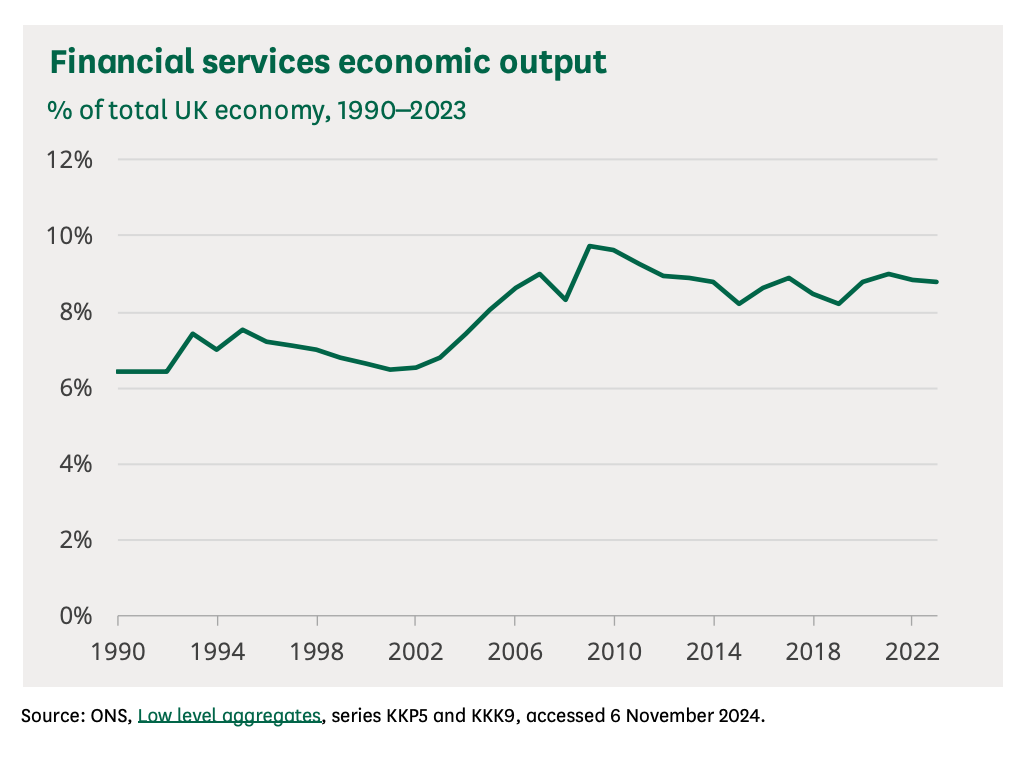

You can see this trend play out when you conduct technical analysis (AKA the science of overinterpreting trendlines in a way that affirms your priors).

The biggest single jump in UK financial services’ contribution to the economy in recent years came in the early 2000s.

This period, however, was far from a golden age for the FTSE.

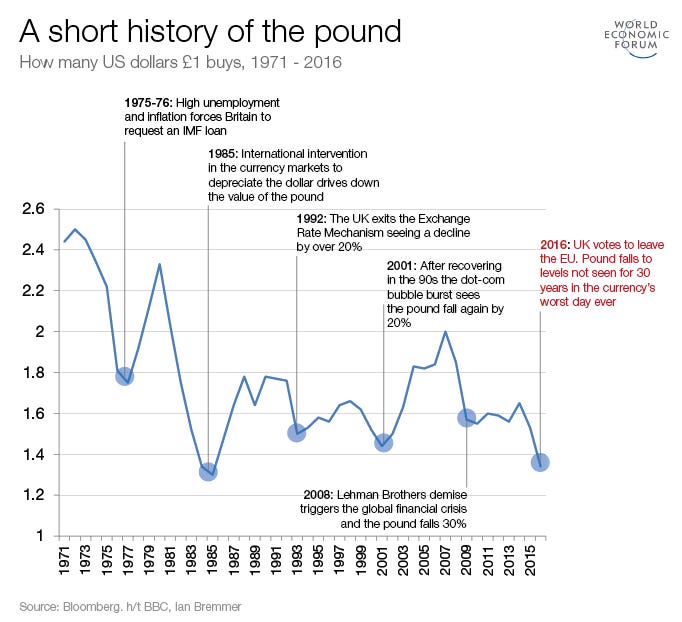

The bursting of the dotcom bubble triggered a slump in many UK stocks, while the strength of the pound against the dollar (the product of lower US interest rates) depressed the international profits of UK companies.

But financial services benefitted from investor uncertainty about the new Euro, the absence of the recession that hit the US and EU at the turn of the millennium, and the growing popularity of cheap mortgages and complex derivatives. We won’t dwell on the last point….

In short, the sector’s growth spurt came from certainty, financial innovation and robust economic growth. The sector hasn’t really grown since then, even as the FTSE recovered - possibly because these have been absent…

The commentary about the LSE is primarily driven by the businesses who do need UK equities to do well to get paid. When you see bananas policy ideas (e.g. the removal of tax-free allowances from overseas shares), the proponents tell on themselves.

These banks and asset managers get an outsized share of voice for a few reasons: i) people who complain tend to get noticed more; ii) the LSE is visible, symbolic target of lazy discourse; iii) hardworking derivatives traders probably don’t regularly ring up journalists to tell them how much money they’re making.

But ultimately, investors and pension funds should be investing in the highest-returning assets, wherever they are. The industry doesn’t have a moral responsibility to prop up UK assets no one else wants.

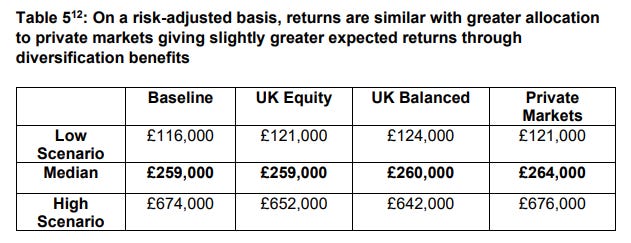

In fact, the government’s own analysis of its reforms designed to mobilise pension funds finds that greater UK equity allocation would drive no increase in returns, while more exposure to unlisted assets would result in only a 2% uplift over 30 years (with a considerable degree of uncertainty).

“Selling the crown”

If we put the grumbling UK asset managers to one side, I can’t help but wonder if the discussion about the LSE is really just a proxy for something else. A sense that either big companies aren’t staying British or being built in the UK at all.

I have little sympathy for the former concern, but some for the latter.

I can definitely see the argument for not wanting Chinese buyers to control our steel or nuclear industry. These are strategically important assets, and it’s faintly mad that UK governments allowed this to happen in haste, only to repent in leisure.

But when it comes to technology - I’m less sold on the notion that acquisitions from companies based in friendly nations is a bad thing, especially if they maintain a meaningful presence here.

Often the argument seems to boil down to, well, vibes. Companies should have a Team GB stamp on the side and that’s just a good thing. Government should intervene to prevent the stamp from being replaced.

We see this play out most prominently in debates around the sale of ‘UK success stories’, like Arm or DeepMind.

But this argument is usually grounded heavily in hindsight bias.

When Google bought DeepMind in 2014 for £400 million, there was no real controversy around the deal. While DeepMind’s early application of deep reinforcement learning to Atari games was known among AI researchers, the company was largely unknown to the wider world. And it didn’t want to be.

Coverage of the acquisition emphasised the company’s obscurity. For example, TechCrunch noted that:

“But the company may also have to clarify what exactly DeepMind’s AI tech does. The company’s site currently just has a landing page, with a relatively vague description that says DeepMind is “a cutting edge artificial intelligence company” to build general-purpose learning algorithms for simulations, e-commerce, and games.”

There was no clamour to keep DeepMind British until it became highly successful years later.

Before being acquired by Google, the company hadn’t raised a penny from UK investors. This wasn’t because UK investors looked at the company and passed - it’s because DeepMind didn’t pitch them.

Early profiles of the company noted that co-founder and CEO Demis Hassabis specifically decided he wanted to raise money from Peter Thiel. He probably felt that the co-founder of PayPal and Palantir could contribute more than a London-based generalist SaaS VC. How dare he.

And had the government intervened to force DeepMind to ‘stay British’, would the company have turned out for the better? Would it have been able to pursue the same ambitious long-term scientific research? Would it have been able to largely avoid commercial pressures? Demis’s talent notwithstanding, almost certainly not.

Despite having Google stuck next to its name, its team is based in London and makes a vital contribution to the local ecosystem. It supports academic research at UK universities, and members of its team are angel investors or have founded their own businesses. This is exactly what we should want!

Returning to our earlier Arm example - the company was undoubtedly a UK success story. But Softbank bought Arm at a 43% premium on the share price - if UK investors thought it had more potential, they didn’t show it.

When Softbank came to list the company on Nasdaq, no one thought the company merited its now $150 billion market cap. In fact, the consensus opinion among the commentators ahead of the 2023 IPO was that Softbank’s target of $50 billion was too high.

Softbank also helped ARM invest in R&D and significantly grow its headcount, while the company diversified beyond mobile, leading its revenue to increase.

As with DeepMind, the M&A opponents blithely assume the business would have achieved the same success or value independently.

It’s also completely legitimate to ask questions about the company’s current valuation, which is likely being inflated by a couple of points.

Firstly, by investors seeing Arm as a way of getting cheaper AI exposure than NVIDIA offers (even though historically little of the company’s business has been focused on AI…). Secondly, by only listing 10% of its stake in the company, Softbank has introduced a degree of artificial scarcity. This is likely why Arm’s soaring valuation hasn’t been reflected in Softbank’s shares, which currently trade at a 60% discount to the net value of the company’s assets.

With Arm remaining a global company and headquartered in Cambridge, the UK has captured plenty of the benefit. The LSE lost a dollop of listing fees, while UK investors missed out on Arm’s gains. But … that’s their fault! Softbank was prescient and saw more potential than they did, and was rewarded for it. That’s how markets are supposed to work.

The next trillion dollar company?

So if the common examples of British buy-outs don’t tell us anything, should we be concerned about the lack of big, new UK companies?

Probably.

It’s not politically fashionable to say this, but small businesses are not the backbone of the economy. They are more likely to employ outdated management practices, are less competitive, spend less on R&D, and pay less in tax.

A company like Ozempic-maker Novo Nordisk, makes a significant contribution to the Danish economy, because it has been able to achieve scale and win internationally. As a result, they paid $2.3 billion in tax last year and were the primary drivers’ of Denmark’s 2% GDP growth. Their contribution unlocked record spending on defence and infrastructure. Booming exports have led Denmark’s central bank to keep interest rates low, making mortgages more affordable.

It’s an extreme example - but it’s hard to argue that several smaller success pharma companies would have had the same positive effects.

A UK ecosystem full of start-ups that struggle to scale beyond Series A isn’t something to be celebrated.

But I think UK enthusiasts can go too far the other way.

Back in May, then Chancellor Jeremy Hunt described his “yardstick of success” as the emergence of a $1 trillion UK company.

I criticised the framing at the time, and various VCs on X told me to “read the room” and stop hating ambition - but I think the framing’s America-brained and actively unhelpful.

A UK company worth £1 trillion would be worth about a third of the UK’s nominal GDP. Even if such a company were possible, it would pose huge systemic risk. It would hold our entire political system hostage. There are already concerns about Novo Nordisk posing a “Nokia risk” to Denmark - a reference to how the collapse of Nokia’s mobile business tanked the Finnish economy.

The US is a significantly larger economy, with a greater population, more top-tier academic institutions, and deeper markets. I’m not saying the US is necessarily proportionally better on these metrics (although it probably is on a few of them) - but there’s obviously a significant advantage in mass that we can’t replicate.

It is much more reasonable to ask why the UK doesn’t have Novo Nordisk-style companies, with a value in the £250-400 billion range.

I’ll probably return to this in more depth in future, but a few reasons stand out.

Firstly, it’s just harder. I’ll spare you vibes-based cultural anthropology in this post, but if you are building in a smaller economy, your ceiling is lower. By contrast, it is possible to build a successful US-based business that doesn’t export meaningfully.

For example, a company like Robinhood, which has essentially only ever operated in the US up until now, has been able to find close to 25 million customers, and has a market cap of over $30 billion at the time of writing. This isn’t to say Robinhood had it easy or didn’t work hard, but a UK-focused brokerage would have to sign up close to two-thirds of the working-age population if it wanted 25 million customers.

To get to the tens of, let alone the hundreds of, billions - requires the ambition and ability to not only win at home, but to beat homegrown competitors in overseas markets.

If we look at international UK success stories, certain trends emerge.

Revolut, for example, was a beneficiary of the UK’s light-touch regulatory framework for fintech (e.g. around financial data access). The e-money licensing framework enabled fast market entry. If the company had attempted to launch in the US, it would’ve been forced into an arrangement with an established player with a banking license. This may well have involved some form of revenue share agreement.

Other successes, like Arm, Darktrace, or DeepMind reflect the combination of long-standing areas of academic strength in the UK with good entrepreneurs and vast sums of money.

Is there anything we can do to ensure this becomes more common?

Some of it, as investor Ian Hogarth argued in a recent FT essay, does require a better, more ambitious class of investor. The UK government seemingly endlessly subsidises generalist SaaS VC firms irrespective of their performance, but if you’re a solo entrepreneur looking to start a fund? Forget it. None of these schemes are open to you.

In other cases, it’s a case of the government getting out of the way. This is part of the Revolut lesson.

It’s common for champions of Europe to argue that US taxes or regulations are as onerous or worse.

And it’s true. The US enforces antitrust aggressively, and capital gains tax in California is higher than it is in the UK.

But remember the scale point. The US can get away with being bad on these questions, because it’s the US. When your market is smaller, the bar is higher. You should assume talent will want to move to the bigger market, because of its existing dominance, networks, and capital. That means we have to fight hard to keep it here! Entrepreneurs need to think “I’m building X, my ambition will be to scale this globally, but it’s easier to start it in the UK”. But there’s no point getting upset with the LSE not competing with Nasdaq - of course it doesn’t!

The key for this will lie in structural or regulatory reform. Not in more subsidy schemes. It’s also likely that many of these reforms would be politically difficult to swallow.

Potential measures like deregulation, lower taxes, and reduced employment protections are all highly contentious and come with trade-offs. There’s also no guarantee that they would work. But I’m sceptical that there’s a magic, pain-free policy lever that we can pull that simultaneously preserves the UK’s current economic model while creating a new generation of mega-companies.

Unfortunately, successive UK governments have instead presided over a stagnant economy and political chaos, while scratching their heads about people making rational business decisions.

So, should we save the LSE?

We started the piece with the LSE, before proceeding to declare it irrelevant. Does the UK’s declining stock exchange have a role to play in all this?

The Tony Blair Institute and Onward recently published a report calling for UK capital markets reform, which recommends closing down the AIM, reducing the burdens on small fund managers, and making listing cheaper and quicker for companies.

These measures are likely all sensible and I see limited downside in pursuing them. At the same time, I suspect they’re only going to make a marginal difference to the LSE. In our new world where companies start in Britain and expand globally, I suspect the majority would still rather list on the NYSE or the Nasdaq, and that’s fine.

But, if the LSE doesn’t play host to the next £250 billion company, the kind of reforms the TBI outlined might help it play a different role. We can probably learn something from Sweden’s example. Swedish global success stories like Spotify are listed in the US, but their domestic exchange acts as a source of capital for smaller businesses. In Sweden, it’s cheap and easy to list a company, you have a willing and motivated retail investor community, and competent asset managers who aren’t snooty about luring small to mid-sized companies from abroad.

As I said in my defence piece a couple of weeks ago, officially accepting the UK isn’t always going to be ‘world-leading’ at everything isn’t good for pride - but it would make designing good policy significantly easier.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer (Air Street Capital), whoever manages my pension, or anyone happens to live in London. This is not financial advice. Don’t arrange your finances based on strangers’ Substacks. Somewhat damningly, I hold no shares in individual LSE-listed companies, but am invested in a UK index fund, while Lindsell Train used to charge me high fees to deliver multiple quarters of benchmark underperformance. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Good example with DeepMind