The late Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski was mainly known for his detailed work on Marxism and theology. But in 1986, he wrote a short thought experiment for literary magazine Salmagundi. Entitled “The Emperor Kennedy Legend”, it envisioned a world, thousands of years in the future, where most traces of humanity’s past had been wiped out by a Great Calamity. Only a handful of books and academic journals from the previous era survived the floods and explosions.

Assembling scraps of information about the life of John F Kennedy, various historians and anthropologists had concluded that the Emperor Kennedy was a likely mythical figure that primitive people in the Before Times worshipped. Kołakowski describes how approximations of Freudians, Marxists, and structuralists in the post-calamity world projected their own theoretical interpretations onto the three or four pieces of evidence about the Kennedy Legend. Maybe Emperor Kennedy’s life was a reflection of class struggle, binary male-female oppositions, or the eternal fear of castration?

At no point in the debate, do any of the participants stop to question their assumptions, whether or not their shared understanding of the facts is true, or if there may be some evidence that they’re missing.

Policy brain

When I’ve written critically about current government policy, friends have reasonably asked “so, what would you do instead?”. On some questions, my answer is “well… nothing”.

If you write about policy for a living, you are predisposed, unless you are one of the world’s six remaining libertarians, to believe that most problems have policy solutions. There is a lever, which people in power can pull, to ameliorate problems or drive progress.

My contention is that this outlook can produce a bias towards action, any action - irrespective of whether it’s actually helpful.

A good example is the debate around why so few British start-ups scale domestically. In my view, scaling challenges reflect a mixture of economic logic, ecosystem immaturity, and the lack of repeat founders or founders turned investors. This will probably improve by itself, to some degree, over time, and much of what we do in the intervening period is expensive displacement activity.

If you look at this challenge through the lens of what I call Policy Brain, the prospect of waiting becomes unbearable. You’ll desperately scrabble around to find some levers to pull, even if few good ones exist. This will result in commissions, taskforces, and new pots of money being pulled together. A mafia of vested interests will coagulate, using the scaling challenge as an excuse to lobby for money or advantageous policy change.

It’s the economy, stupid

Policy Brain, however, isn’t just the impulse or blindspot of some idealistic nerds. It’s a reflection of economics.

Ultimately, research costs money and someone needs to provide it. That may be a donor or a sponsor for a think tank, or a fixed budget for an in-house policy team.

The people spending this money expect it, directly or indirectly, to have some influence on the world. This does not incentivise the publication of research rejecting interventions or proposing masterly inactivity.

Many researchers will naturally assume that this is either not what their benefactors or their boss are paying for. “We took a long hard look at X and while we agree it’s bad, we’re not convinced we can do much about it” or “we’ve had pet theory Y for ages, we tested it and by every conceivable metric it sucked” are both hard sells for different reasons. This is one driver of the huge volumes of low value policy work that Anastasia and I wrote about last year.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

We’ve seen this movie before

The closest parallel to the problem of policy filler comes from the world of scientific publishing. There has been a long-standing push to encourage the publication of more null results - research where the findings don’t support the hypothesis being tested. One 2022 survey suggested that 75% of scientists were willing to publish null results, but only 12.5% had been able to do so.

In short, this is because peer-reviewed journals see them as bad box office.

In a world where academic researchers are cautioned to publish or perish, this creates some obvious perverse incentives.

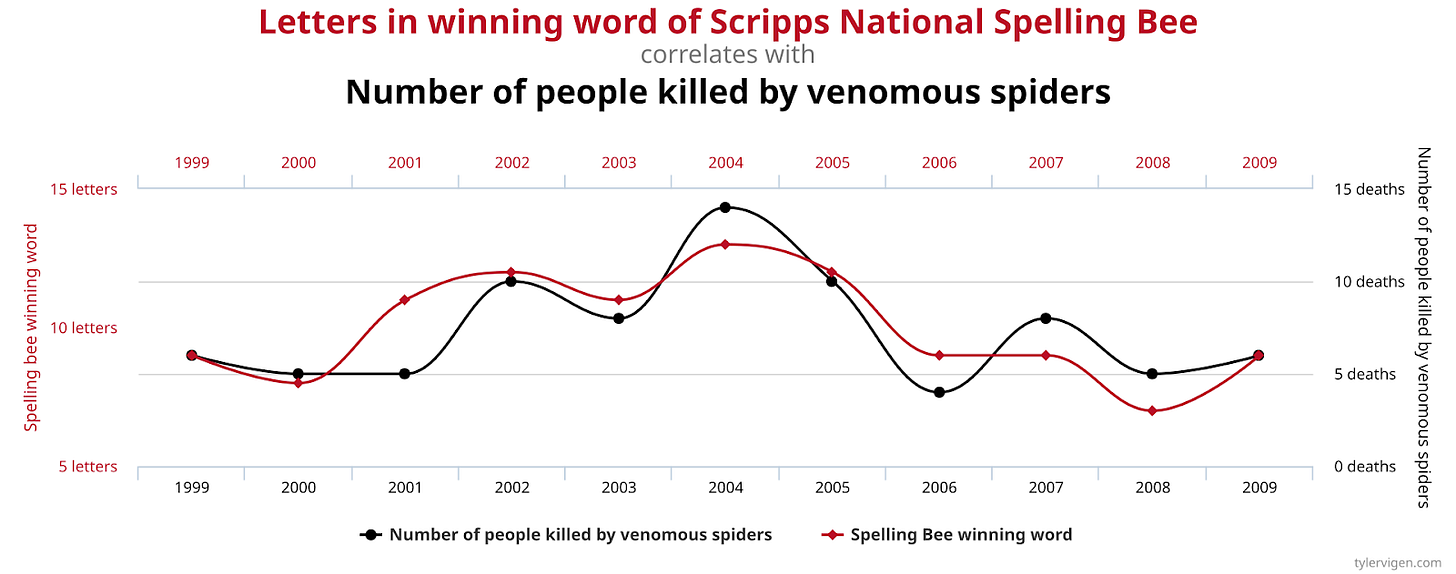

This has led to widespread use of practices such as p-hacking, where researchers misleadingly produce statistically significant findings. This is actually surprisingly easy to do. One form of p-hacking is the misuse of subgroup analysis - where you examine the effects of an intervention or treatment on specific subsets of study participants (like age groups, genders, or other demographic categories).

If you analyse enough subgroups, you are likely to find some statistically significant results by sheer chance. For example, if you test 20 different subgroups at a 0.05 significance level, you have a 64% chance of finding at least one "significant" result, even if there's no real effect. Minus out the other 19 groups, and voilà, your statistical noise has become a valuable new contribution to the literature.

This practice is a staple of the bad research The Studies Show, one of my favourite podcasts, digs into on a regular basis.

This kind of bad practice helped fuel the ‘replication crisis’ - the dawning realisation that scientists are simply unable to reproduce reams of eye-catching findings. Power posing, much of the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the brain-enhancing effects of listening to Mozart all fall into this category. This phenomenon started in psychology in around 2011, but has spread much further.

This has led to a push for the greater publication of null results, along with the use of pre-registration, where researchers publicly state their hypothesis and how they plan to test it, before conducting the work. This makes it harder (although not impossible) to magic a hypothesis into existence retrospectively through statistical sleight of hand. This does of course comes with trade-offs, such as the potential loss of the serendipitous discoveries that come with open exploration.

There’s also growing interest in the idea of Registered Reports. In this system, researchers get feedback on their methodology before conducting research. Provided that it is then executed faithfully, the journal will publish the resulting study, even in the event of a null result.

This isn’t just good for integrity, it advances the field. If you work in any discipline, you might be interested to know if someone smart has constructed a hypothesis, only for the evidence not to support it. After all, this null result might inform how you approach the same question.

Losing this data to a tidal wave of filler and spurious correlations impoverishes everyone.

Politics vs policy

One disadvantage that policy suffers from that (most) science (usually) doesn’t is the impact of politics. Legislators want to legislate. The bias is almost always to do something, or at least to be seen to be doing something. Earlier in my career, I was given the advice that if you wanted to stop a politician from passing a law, it’s not enough to prove it’s a bad idea. Instead, you have to find something else for them to do.

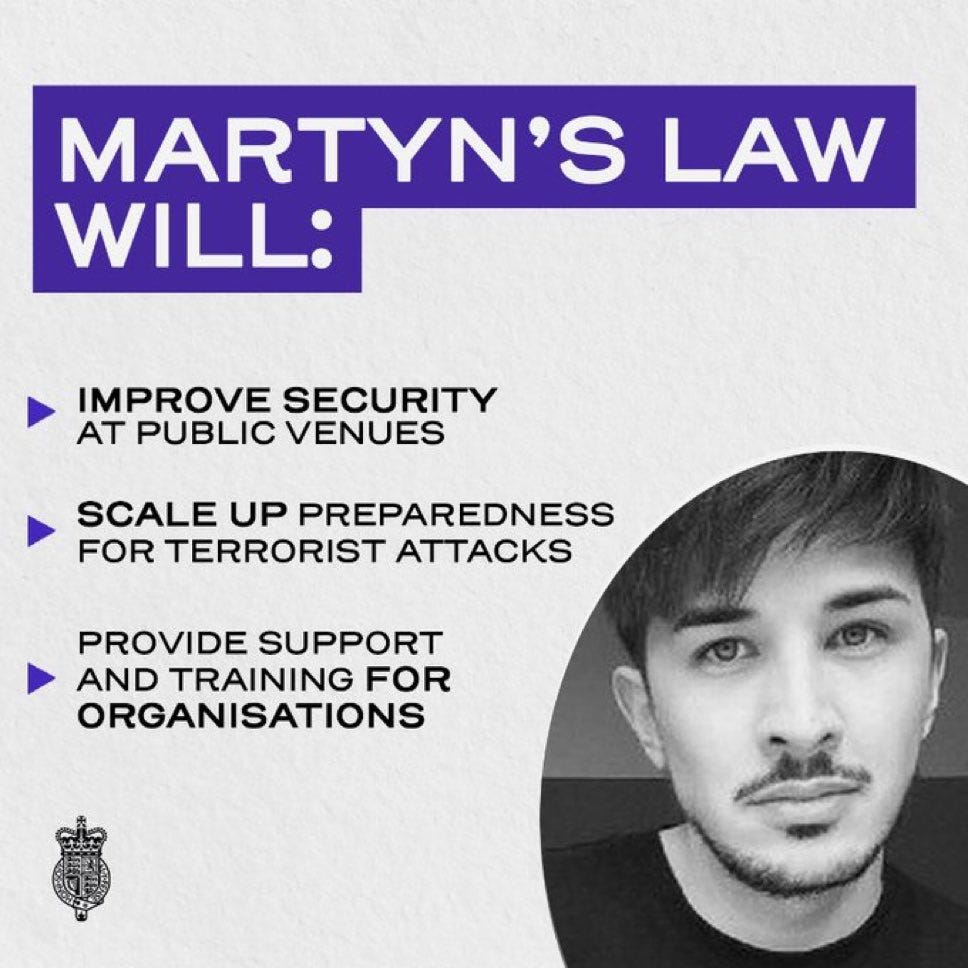

This impulse has produced no end of questionable legislation. A recent example is “Martyn’s Law”. The Terrorism (Protection of Premises) Bill 2024 is legislation currently under discussion in the UK, which was drafted in response to the 2017 Manchester Arena Bombing.

The inquiry following Manchester found that the attack could have been prevented. The security services were overstretched in the run-up, and there were a number of critical failings on the night. These included police officers disappearing for twice their allotted break time, a security guard failing to escalate a report of a suspicious person, and another security guard being too afraid to approach the suspect out of fear of appearing racist.

This is all deeply regrettable. Unfortunately, the security services can make mistakes. Police officers and security guards can make bad spontaneous decisions. Organisations should urgently study what went wrong and draw lessons from it. But not everything bad that happens to the public is a public policy question. Laws can’t drive the rate of bad decisions by individuals down to zero. Nevertheless, the government decided to legislate.

The resulting bill imposes a tiered set of requirements on venues, starting at those capable of holding over 200 people, to introduce measures to reduce the likelihood of terror attacks and implement response plans. At the cheap end, this will mean more form-filling and training. At the expensive, new infrastructure. The burden would disproportionately fall on smaller, community venues.

The government’s own assessment of the policy’s Net Present Social Value (its metric assessing the costs and benefits of a policy) suggested that it would contribute a cool negative £1.8 billion. To be clear, this measure takes into account the potential lives saved.

Martyn’s Law isn’t the only example of ‘something must be done’ policy-making. You could count the Online Safety Act, the independent football regulator, regulation on window size in newbuilds, proposals to blunt kitchen knives, and almost every policy recommendation to fight misinformation ever. We’re really good at this.

Closing thoughts

Of course, people working in policy can’t stop politics. But they have a responsibility not to fuel the flames with yet more filler. A proposed extra form or assessment here, an additional compliance check there, or a new government office for counting badgers can all have unexpected and costly downstream consequences.

Null results can be useful for the policy practitioner as well as the scientist. If a team you respect has conducted an economic analysis or consulted people with frontline experience, and concluded that there isn’t a short-term fix, the real problem lies elsewhere, or a fashionable intervention may be less effective than it appears - that’s useful.

Policy people should also have enough confidence in the value of their work to make this case to their employers or donors. Publish your ideas that didn’t work out on closer examination. Say when you think there’s no good answer. Otherwise, we may as well spend our time attempting to crack the Emperor Kennedy Legend.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer, traffic wardens in my local area, or anyone else. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Image credit: data dredging - https://www.tylervigen.com/

PS: if enough people send me some good null policy results that they haven’t been able to use, I’m up for publishing a collection. Hit reply or DM me.

Superb piece. Instant follow!

the window size issue is not as simple as the twitter poster suggests. It is true that guidance (not building regulation - the guidance just suggests one way of how you might meet the regulation) is pushing windows to be smaller. But there are a number of factors behind this, and a big one is energy reduction. Guidance in Part L is suggesting improved airtightness and higher insulation standards in walls, doors and windows. If you put these together with large windows you can get overheating through solar gain on warm days.

This doesn't have to be a problem - you could install a mechanical ventilation system. With a powerful enough one you could have a massive window and solve the safety problem by not having an opening in it. But MHVs are expensive, as is highly insulated glazing, so housebuilders lobbied Govt not to include them in the new Part O and continue to recommend purge ventilation (opening a window). The result is having a smaller glazed surface area in the property.

Unsurprisingly housebuilders like the one quoted in the story the twitter poster used like to tell a different story.